Mr Owl and his wife had invited Mr and Mrs Badger to afternoon tea. And a very good tea it was too. There were three kinds of bread: white, brown and currant. There were Madeleines, doughnuts, Swiss roll and rich, black fruit cake. And, of course, there were sticky buns.

After the meal, Mrs Owl and Margaret Badger retired to the kitchen to do the washing-up. And Owl and Badger settled down in capacious armchairs in the lounge and lit their pipes.

Nearly forty years ago, my father – who was an army bandmaster – was visiting the studios of the British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS) in Cologne, when he bumped into a man in late-middle age who had pink-rinsed hair and was dressed in full scoutmaster uniform. The costume, it turned out, was the man’s normal outfit for when he was broadcasting.

That’s a little odd in itself, but it becomes more peculiar still when you remember that at this stage BFBS didn’t have a television service. These clothes are what he wore for broadcasting on the radio.

The image that was conjured up for me by my father’s account is one of the reasons why I’ve been fascinated for so long by the figure of William Charles Boyden-Mitchell, better known as Bill Mitchell, and better known still as Uncle Bill. Not my uncle, you understand. He was everyone’s uncle, a radio uncle, the kind who presented children’s programmes.

Now a website called BFBS Radio Show Archive has posted a collection of 62 recordings of his children’s stories, taken from his own broadcasts, and, to my great joy, I find that the stories are every bit as peculiar as I remember them.

But to begin at the beginning…

I was too young for Children’s Hour, the most celebrated children’s show ever broadcast on British radio. Starting in 1926, it had a good run, but it came to an end in 1961, the year before I was born. And anyway, I largely grew up in West Germany, so I probably would have missed it even if it had still been on air.

But no one ever accused the British Army of keeping up with the times, and in the mid-1960s BFBS, which was responsible for satisfying our radio needs, launched its own version of the now defunct programme in the form of Kinder Club. The name came, obviously, from the German ‘kinder’ (children), not from the comparative form of ‘kind’. You’ll note also that the temptation to make it alliterative as Kinder Klub had been firmly resisted; there were standards to be upheld here, as we shall discover.

The presenter was called Uncle Bill, to fit with Uncle Mac and Uncle Peter, the hosts of Children’s Hour. That, at least, had always been my understanding. In reality, I find – on checking Denis Gifford’s invaluable The Golden Age of Radio – that when Children’s Hour started, the BBC had issued an edict that children’s presenters were no longer to be referred to as Uncle and Auntie, so it turns out that, by having an Uncle Bill, BFBS was even more retro than I had previously imagined; we were going back to the earliest days of wireless.

My memories of Kinder Club are a little vague. I think it followed the established pattern by having readings of classic children’s stories, as well as birthday greetings and the like. It certainly featured music, though not necessarily what we wanted to hear. I remember being slightly baffled even then by the way that the music seemed so highbrow. Mozart was a particular favourite, though sometimes there’d be a military march or suchlike, and occasionally – very occasionally – Uncle Bill would announce that, as a special treat, we were going to have some pop music. This normally turned out to be Henry Mancini’s ‘Baby Elephant Walk’ or a song from a Disney cartoon of the 1950s.

My main memory, however, is of Uncle Bill himself, who was weirdly, cosily hypnotic in the way that children’s broadcasters generally were, back when adults were employed to do the job. They tended to be remote yet conspiratorial; on your side – so long as you were good – but never pretending to be part of your world. The familial title was wrong though (which may be why the BBC dropped it): they were much closer to being grandfather figures than uncles. Certainly Uncle Bill was.

According to an article published in The Times in February 1975, Bill Mitchell was then 52 years old, which would take his probable date of birth back to 1922. That would make him more than a decade senior to my parents, but even that doesn’t seem enough; he gave the impression of being a dozen years older still. The same piece said that, in addition to his duties on Kinder Club, he was a continuity announcer on BFBS (which I knew) and the senior programme assistant to the station, which I didn’t.

And, inevitably, reference is made in the article to his Stories from Big Wood. Inevitable because they simply couldn’t go without mention. Written and read by Uncle Bill himself, the Stories from Big Wood were the brightest, most sparkling jewel in the Kinder Club crown. These were what he was really known for.

‘The stories,’ said The Times, ‘reflect a nostalgia for an England which, if it ever existed, ceased to do so many years ago. But then Mr Mitchell has lived abroad for 26 years and does not want to return to what has become an alien land, he told me.’

What the paper was hinting at is that Uncle Bill’s work was thoroughly reactionary in its view of society, and just as thoroughly unapologetic about the fact.

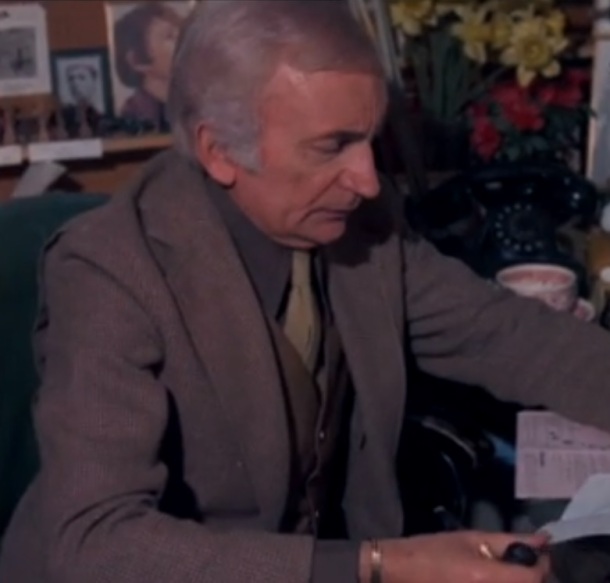

Uncle Bill Mitchell

Big Wood was a fully realised little world, centred on a lake around which were several settlements. The largest was Town Wharf, while others included Needle Cove and Hollow Tree Wharf. The oldest community of all, though, was Big Wood itself. And here lived our heroes: the slightly pompous and somewhat tetchy Mr Owl, and his good friend Mr Badger, ‘a level-headed, dyed-in-the-wool, straight-as-a-die sort of person’. Their adventures and doings were lovingly chronicled by Uncle Bill in stand-alone episodes of 12 to 14 minutes each, in a series that ran for well over a decade.

So you’ve got Big Wood, and you’ve got Owl and Badger, and you assume that this is an attempt to revive the golden age of children’s literature, some kind of knock-off of Winnie-the-Pooh and The Wind in the Willows. Which is correct, but only up to a point, because Uncle Bill had his own furrow to plough.

To start with, both Owl and Badger are married. Their wives are called, respectively, Maude-Rose and Margaret. And that means that the tone is more domestic than derring-do; there’ll certainly be no weird Piper at the Gates of Dawn interlude here, with the friends sailing up the river to meet the Great God Pan. More than that, though, classic children’s stories seldom feature married couples. Roo in Winnie-the-Pooh has a mother but no father, as does Peter Rabbit in Beatrix Potter’s story, and similarly, in the human world, there are absent fathers in Swallows and Amazons and in The Railway Children.

In this context, Mr and Mrs Owl are not normal. And even though the one reason why you might want married couples in a children’s story is to allow for young characters, both the Owls and the Badgers are childless. We have families without inter-generational relationships. Indeed pretty much all the major characters seem to be middle aged.

Then we have the fact that these animals behave just like human beings. This goes far beyond the anthropomorphism normally encountered in such stories. Most writers make some attempt to refer to the animal nature of characters: Pooh, being a bear, likes honey, for example, and Eeyore eats thistles, while Rabbit lives in a rabbit hole, just as, in The Wind in the Willows, both Mole and Badger have their homes underground. In the latter story, when Toad recovers from having a little weep, he signals his return to normality by declaring, ‘I am an animal again’.

There’s none of that nonsense in Big Wood. The Owls and the Badgers, and everyone else as well, live in proper two-storey houses, with gardens that have lawns, flower-beds and greenhouses, and are surrounded by wooden fences.

They eat porridge and toast-and-marmalade for breakfast, and Lancashire hotpot followed by spotted dick with custard for lunch. They drink hot, sweet tea at every possible opportunity, preferably from Mr Owl’s silver tea service, as well as cocoa in winter, and lemonade in summer, though on a special occasion they might run to a small sherry. A description of a picnic tells us they had: ‘Ham and egg sandwiches with lettuce and mayonnaise and cups of hot tea. And then they had two sticky buns each.’

(The sticky buns are something of a motif, Uncle Bill’s signature dish as it were. In a set of stories that rival the Famous Five for their recitations of foodstuffs, you can always be sure that sticky buns will be somewhere on the menu.)

Further, they wear human clothes. Badger favours a brown suit or, if he’s out walking, he might go for ‘a tweed ulster coat with a tweed deerstalker to match’, while Owl, who wears a pink linen nightgown to bed, can sometimes be tempted into formalwear: morning coat, striped trousers, lavender waistcoat, grey top hat and patent leather shoes. He is also described as having arms and legs, and – since he keeps a telescope in his attic – we can assume that he isn’t quite as farsighted as other owls. He plays cricket, and his wife, Maude-Rose, plays organ in the local church.

They are, in short, perfectly normal suburban, middle-class human beings, albeit ones with no children but childishly sweet teeth. They don’t have a single animal characteristic to display between them.

Nor does their environment make any concessions to the animal kingdom. Owl tends to travel in his 1936 Rolls Royce sports coupé, his biplane or his motor launch, but for those who require public transport, there’s a tram and a railway at Big Wood. There’s also a hotel, a theatre, a hospital and a school, as well as a golf club, scout camp and sports meadow. There’s even a castle. Town Wharf, being a more substantial town, has a university, a shopping centre and a cathedral (dedicated to St Pancras, the patron saint of children). The largest building in the area, though, is the newly constructed office-block housing the Big Wood District Council, from where, explains Mr Crow, ‘all the rules, regulations and laws will be issued for the benefit of you, the taxpayers’.

And that language brings you up short. Because it’s definitely a bit odd. Characters in children’s fiction tend not to address each other as taxpayers. And rules and regulations should really be there only so they can be infringed by our adventurous heroes.

But things are different in Big Wood. These are the most thoroughly bourgeois animals I’ve ever encountered. Mr Owl, in particular, is a very important owl indeed: he’s the District Magistrate, as well as being the Colonel of the volunteer Big Wood Defence Regiment, while Mrs Owl and Mrs Badger are leading members of the Big Wood Ladies’ Guild.

Owl and Badger don’t have regular jobs, as far as one can tell, though Owl does have an office in the town hall. The implication is that they have comfortable private incomes. But others are gainfully employed: Mr Hedgehog is a taxi driver, Mr Blackbird is a printer, and Mr Beaver runs a boatyard. Good honest artisans, every man jack of ’em, the kind of chaps who take pride in their work and know their place. Rising up through the social scale we find Captain Rook, Mr Crow (a lawyer), Dr Eagle, the Rev Crested Grebe MA, Major-General Peregrine Falcon, and – the most elevated personage in the whole of Big Wood – Lady Peacock of the Manor House, Town Wharf. Social stratification is terribly important in this world.

Gradually you realise that this isn’t The Wind in the Willows at all. It’s much, much closer to St Mary Mead, the sleepy village where Miss Marple lives (though obviously without all the murders). St Mary Mead lies somewhere in south-eastern England, and Big Wood can’t be very far away. When the residents sing a hymn, it’s ‘Rock of Ages’; when they fly a flag, it’s the Union Jack; and when there’s a new wing of Town Wharf University to be opened, they invite the Queen herself to do the honours, it being Jubilee Week in 1977.

(Actually, there is a Big Wood flag as well. It’s an oak tree on a white background, which makes one wonder whether there was an Uncle Bill fan lurking in David Cameron’s Conservative Party when it chose its new logo in 2006.)

It’s all a lovely, fantasy vision of the England that Bill Mitchell left behind when he went abroad at the end of the 1950s.

But life is not quite as cosy and comfortable and complacent as it first appears for the good burghers and yeomen of Big Wood. Because there’s one element who can always be counted on to disrupt ‘the usually calm and peaceful environs of the lakeside community’. As Nick Cave once sang, there are rats in paradise.

In The Wind in the Willows, our heroes have trouble with the stoats and the weasels who take over Toad Hall and have to be driven out. Uncle Bill took up this image and ran with it. Stoats and weasels, to say nothing of ‘the added menace of the ferrets’, are the bane of everyone’s existence in Big Wood. They’re ‘morons and yobboes’, the lumpen proletariat who need to be kept under control, the criminal element who bode ‘no good for those of us on the side of law and order’.

Ultimately, however, like all bullies, they’re cowards, liable to surrender to authority at the first sign of opposition. The only reason they pose any real kind of threat is that they are so easily manipulated, and because there are ringleaders seeking to organise them. Mr Nightjar and Reynard Fox, for example, are always loitering, waiting to cause trouble, but they are merely the lieutenants to Mr Owl’s great archenemy.

And the choice of animal here is intriguing, because it seems such a definite rejection of The Wind in the Willows. In Kenneth Grahame’s novel, one of the heroes is Rat (who is actually a water vole), but from any proper, right-thinking perspective, you have to conclude that Ratty’s a bit suspect. He has the whiff of the intelligentsia about him. He’s a ‘dreamer’, he ‘sometimes scribbled poetry’, and the Mole is in awe of his intellect: ‘If I only had your head, Ratty!’ he marvels. As a good Englishman, Uncle Bill didn’t trust intellectual types. So he cast his great villain as Water Rat.

Now, Water Rat’s position in Big Wood is never very clear. He’s a criminal, of course. That much is certain. Everyone knows he’s a criminal and he doesn’t seek to hide the fact. So he gets sent to jail on a frequent basis, but – even though he’s evidently beyond rehabilitation – he doesn’t stay there for long and he’s normally back out again for the next story.

Sometimes, he just plays pranks: ‘The criminal element round here are rather fond of the odd hoax,’ notes Mr Badger. Water Rat is the trickster who substitutes a bomb for a cricket ball and gives it to a ‘particularly nasty looking stoat’ to bowl with (a fast bowler, obviously; stoats aren’t sophisticated enough for spin). But at other times, it all gets much more serious, and Water Rat is to be found leading industrial disputes and even armed insurrections, trying to seize power in Big Wood.

Whatever he’s up to, he really riles Mr Owl. Because it’s Owl’s job, as District Magistrate, to ensure that the forces of law and order prevail. So when the Big Wood District Council is ‘accused of apathy and a sort of couldn’t-care-less attitude’, and Water Rat tries to exploit the mood of discontent, firm action has to be taken:

Water Rat and those of his ilk had voiced their opinions by staging demonstrations, which were, needless to say, broken up by Constable Otter on the express order of the District Magistrate, Mr Owl.

For such a small town, incidentally, there’s rather a substantial police force. Despite his seemingly lowly rank, Constable Otter commands at least ten uniformed officers as well as an active Special Branch. Should this not be sufficient, the Big Wood Defence Regiment can always be called upon. In one episode, an operation to break up a gang of ferrets from Town Wharf (who ride around on ‘frightfully noisy motor-bicycles’) sees a hundred soldiers deployed undercover, with a further three platoons at each end of the High Street, and even a tank hidden in the undergrowth. ‘I’ll have the law on that man!’ cries Owl, whenever he hears about Water Rat’s antics, and Constable Otter is always happy to oblige.

Occasionally, Water Rat’s lust for power expresses itself in more conventional form, though even then no decent resident of Big Wood trusts him. When Owl hears that, for the first time, he has a rival candidate in the annual election for District Magistrate, and that it’s Water Rat, he’s horrified at this outbreak of democracy: ‘I’ve never heard anything like it in my life, and that’s a fact and no mistake.’ His mood is not much improved when he hears that Water Rat is aiming for the working-class vote with his campaign slogan: ‘The Man with the People in Mind’.

But then Owl knows better than we do that Water Rat is up to no good, and as the story progresses the incumbent District Magistrate is kidnapped by rascally stoats and weasels acting on their master’s orders. Understandably, Owl is infuriated by his treatment at the hands of Water Rat’s thugs, but even so his choice of words is revealing: ‘I’m going to show that rogue who’s boss round here, and no mistake.’ Again, heroes in children’s stories don’t traditionally refer to themselves as the ‘boss’, and certainly not if we’re expected to side with them.

But there’s no doubting where Uncle Bill’s sympathies lie. Water Rat never wins. He simply doesn’t have the forces to implement his dastardly plans, and he’s always crushed by the power of the state. When he and an accomplice are caught in the act of burgling Mr Crow’s house, Owl ‘had great pleasure in ordering Nightjar and Water Rat to be detained in Big Wood police station for a period of not less than one month with, of course, hard labour’. Several of the stories end like this, with Water Rat behind bars, and Owl and Badger sitting down in front of a roaring fire to have tea and sticky buns.

The class element is surprisingly explicit: ‘Down with the ruling classes!’ shouts a young weasel as the Owls and the Badgers drive by in the Rolls. So too is the denunciation of rebellious youth. Water Rat’s minions are always portrayed as being younger than the main characters, and a running theme is the state of modern youth. ‘They have much too much pocket-money, and there’s little or no discipline,’ concludes Owl, and elsewhere his wife is to be heard in much the same vein: ‘The things that people do nowadays to make life difficult and dangerous is beyond my comprehension. I’m sure it all starts with this rather lackadaisical attitude they have today in regard to discipline.’

And underlying it all is a fear that the stoats, weasels and ferrets may lead the children of Big Wood astray, even the ones who come from ‘perfectly good, law-abiding families’ and are clever enough that they should be heading for ‘public schools and university’.

If these seem like very contemporary concerns for stories that are otherwise seemingly set in a mythical 1930s, then so too is the obsession with political violence. When a mysterious locked briefcase is found on Mr Crow’s doorstep, the immediate assumption of everyone is that it must be a bomb, ‘in view of recent events proclaimed in the newspapers’. It’s perhaps worth bearing in mind that these stories were written for the children of the British Army at a time when their fathers were quite likely to be away on active service in Northern Ireland.

But not everything about the modern world is appalling. The District Council, while clearly run by the Conservative Party, is economically more attuned to Harold Macmillan than to Margaret Thatcher, and still believes in state intervention in industry. At one point it votes to invest in the building of a new lime-works, aimed at exports to ‘foreign parts’, and the opening of the plant gives Major-General Peregrine Falcon a chance to expound on the guiding principles of Big Wood:

Even though we live in the depths of the countryside, we are a modern and forward-looking community. Although we draw the line at plastic cups and cruets, and looking like a collection of scarecrows, we do endeavour, and indeed succeed, in living up to the times. We have resuscitated old buildings and old companies, and given birth to new ones.

That’s Big Wood for you: the Britain that was, and might yet be again, if only we all smartened up a bit, knuckled down to it, and discarded our plastic cruet-sets…

But the trouble with quoting, at whatever the length, is that it doesn’t do justice to the experience of listening. These were stories designed to be read aloud by their writer. And – a little to my surprise – I find on revisiting them that they’re really rather good. Despite the overt politics, despite the incongruous idea of a children’s fiction that celebrates a middle-aged, childless, suburban gentility, there’s something about the tales that works.

That something is Uncle Bill himself – not much of a writer, perhaps, but a very good storyteller. He had a fantastic radio voice: resonant and reassuring, as fruity as one of Mrs Owl’s rich, black fruitcakes. And he used it to give the characters their own identities, voicing over a dozen regulars and even more incidentals. If some sound rather similar to each other, and if Constable Otter is a dead spit of Deryck Guyler’s Potter in Please Sir!, then at least the main protagonists are clearly and engagingly delineated.

The stories were, as far as I can tell, read live on air (coughs and throat-clearings haven’t been edited out), and that takes some doing. With no music or sound effects to lean on, it was down simply to his voice to create an atmosphere.

He achieved that, and consequently the characters came to life. Owl and Badger, in particular, are a convincing and endearing double-act, a little reminiscent of Captain Mainwearing and Sergeant Wilson in Dad’s Army, though in this instance Owl does listen, and generally defers, to Badger’s opinions. Even many of the minor figures work: Miss Nightingale, the head mistress of Big Wood Primary School, may be a stereotype, but you can see her clearly enough, in her ‘two-piece tweed costume, with a dark brown pullover, a string of pearls at her throat, sensible stockings and tan-coloured, flat-heeled brogue shoes’.

I wouldn’t have known then what brogue shoes were, and that points to another strength of the stories. Because at the time these were being written, arguments were emerging about the canon of children’s fiction. Most famously, Enid Blyton was being subjected to strong criticism on the grounds both of her supposed middle-class morality and of her linguistic simplicity.

The first charge could comfortably be laid against Uncle Bill, but not the second. His language is impressively advanced. This, for example, is his description of the noise made when Owl’s nemesis forms a ‘progressive pop group’ called Water Rat and the Water Babies: it was ‘absolutely stupefying, a sheer, gigantic wave of utter and complete cacophony. The windows rattled and the throb of the din was shattering in the extreme.’ You’re more likely to find a challenge to your vocabulary than to authority in these stories.

Uncle Bill in his office

As a child, I enjoyed listening to the chronicles of Big Wood, and I’ve enjoyed listening to them again. It would be going too far to say that I loved them, and they weren’t my favourites – apart from anything else, I always preferred reading to listening. Nor am I claiming that they’re great stories, or that Mitchell is truly fit to be mentioned alongside Grahame or Milne. But they have a charm and so does he.

How popular they were with other children, I don’t know. Officially BFBS only broadcast to around 200,000 servicemen and their families. In reality, it got a daily audience of between five and eight million, attracting listeners from both West and East Germany, the Low Countries, Denmark and Poland. How many of them tuned in to Uncle Bill is anyone’s guess – as is the impression they would have got of Britain if they did listen.

Big Wood did, though, have a cult following in some parts of the army, particularly with young officers, many of whom used the characters to provide nicknames for each other. The BFBS Radio Show Archive site includes a story that in the mess of the 9th/12th Lancers in Hohne, officers would have a drinking competition during Kinder Club, the winner being the one who consumed the largest quantity of scotch during the telling of the Big Wood story: the champion was ‘a renegade ex-Rhodesian Forces Special Forces officer who managed a whole bottle’. Bill Mitchell was said to have been a serious drinker himself, so he may have approved of that.

And, representing the other ranks, I like this testimony from an army driver named Nobby Clarke:

Good old Uncle Bill and his tales from Big Wood, with those nasty stoats and weasels. Sitting on your bed with two big chip-butties from the cookhouse and a mug of tea, shouting at the radio: ‘Go on, Mr Owl, bash him!’ and other such army phrases.

The other story that appears on army bulletin boards, where Uncle Bill occasionally receives a mention, is the rumour that he got sacked by BFBS for leaving his mike on slightly too long at the end of a broadcast, so that his sign-off (a cheerful ‘Goodbye children’) was followed by a muttered: ‘Little buggers.’ Or variations thereon.

I don’t believe this. I’m sure he had no great fondness for children, as many children’s entertainers don’t. I’m happy to see him in the same mould as, to take a fictional example, Leslie Dwyer’s misanthropic Punch and Judy man in Hi-de-Hi! The story about the open mike, however, seems too pat an example of the urban myths that always surround children’s shows.

It is true, though, that Bill Mitchell did get sacked by BFBS – in 1980, as I recall – but I think it was simply because he’d outlived his time there. He was too remote and posh, too old-fashioned even for the British Army. His attitudes and approach were already dated in the mid-1960s; fifteen years on, he’d become an embarrassment.

What had at one stage been an hour-long programme had by the end been whittled down to five minutes a day, lost deep in the afternoon show, a relic of a bygone era, almost entirely buried under shovelfuls of the pop music he despised so much. And no one was listening anymore. Towards the end of his time on the station, he held a painting competition for children, and had to extend the deadline by a month because he had received not a single entry.

Even so, his dismissal came as a horrible shock to him. He took it very badly. So much so that his bosses didn’t trust him to maintain a professional attitude, and he had to be tricked on his final broadcast – he thought it was going out live, but actually it was being recorded, so that it could be edited before transmission. Instead he made his feelings clear in a tear-stained interview he gave to Sixth Sense, the weekly newspaper for the British Army on the Rhine. His life, he explained, was now effectively over; there was nothing left for him but to retire to Bournemouth and die. It was heartbreaking stuff.

Admittedly, I now know from The Times that he could only have been in his late-fifties at the time, which in retrospect makes his response seem perhaps a little melodramatic. Maybe the Sixth Sense journalist caught him in maudlin mood. Anyway, it all seemed terribly tragic back then. So much so that my mother, who was helping to organise some kind of jumble sale on camp, invited him to come and open it, so that he’d feel he was still wanted.

Which is how I got to meet Uncle Bill. Slightly to my disappointment, he was wearing a three-piece suit, rather than the scoutmaster’s uniform, but I was very polite nonetheless and told him how much I liked his stories. I got his autograph and he gave me a map of Big Wood. Well, I don’t suppose he had any further use for them.

After that… I know nothing. I have no idea where Bill Mitchell came from, nor where he went. And I had thought that he left little trace. His stories were never published in any form at all, so far as I’m aware. Of those who did listen to him, the vast majority, I assume, won’t have given him a thought in many years.

I haven’t found any appreciations of his work on the internet, and that mention in The Times is the only reference to him I can find in newspaper archives. But now those stories of his have been posted online. Which is wonderful, because I think he’s worth remembering, if only as a footnote to an era of children’s broadcasting that effectively ended before I was born. And for the fact that a couple of generations of service children grew up listening to him.

I assume that Uncle Bill’s no longer with us, but it is just possible that he may still be alive, now in his nineties.* In any event, I’d like to believe that his unsought-for return to England, to this ‘alien land’, wasn’t quite as awful as he feared. I suspect, however, that that’s wishful thinking, born of sentiment.

Far more likely that he would have concluded that not even sticky buns were as good as they used to be. And, as he drank away his last days, he would have snorted, as did Mr Owl: ‘Lack of discipline! I really don’t know what the world’s coming to!’

Some of Uncle Bill’s scouting memorabilia, from the wall of his office at BFBS Radio, Cologne

* I’m grateful to Wayne Gardner for the information in the comments below that Bill Mitchell died in Norwich in 1988.

Update: A Wikipedia page has now been created for Uncle Bill and reveals that he died in Norwich in 1988, the year of his 66th birthday. On behalf of all Uncle Bill’s followers, I offer my thanks to Tania Cordeiro for creating the page.

Wonderful memories. The ‘Tales’ are to be uploaded to Archive.org – the Internet Archive – for perpetuity. And it would be great to get further stories. There was at least one ‘official’ cassette tape issued. Does anyone have an image of the map of Bigwood?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Memories indeed…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Ginge in Germany and commented:

For all the pads brats out there…

LikeLike

I grew up in Gutersloh in the early 70s listening to BFBS, and loved Big Wood stories.. My parents still have a few of the stories recorded on cassette which they would play to us kids in the back on long car journeys, but none of us has anything to play them now! I have searched several times over the years for anything about the Big Wood stories or ‘Uncle Bill’ but apart from a few mentions on forums, nothing. Finding this blog and these archive recordings is like finding a piece of my childhood again, 45 years on.

LikeLike

Uncle Bill picked my soap box cart as the best made one at a fete in Sennelager in 1975. He was wearing his scout uniform. He handed me my prize, which was a thermometer (encased in faux brown leather!) and he came across as quite grumpy as I remember. I was 10. I grew up listening to Big Wood. This article is amazing. I wonder what happened to him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He died in Norwich in 1988, the year of his 66th birthday.

LikeLike

I’ve added a footnote to the piece, thanking you for this information, Mr Gardner. Alwyn Turner.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for this information! I have been trying to access the recordings of the Big Wood Stories, and they were apparently available on these sites:

http://bfbs-radio.blogspot.com/2014/06/at-long-last-big-wood-tales-have-been.html

http://bfbs-radio.blogspot.com/p/asters-sunday-breakfast-last-edition.html

However, they default to this site, and there is no link from there:

https://radiointernational.blogspot.com/

Could you help me find them? I have often cited “Mr. Hedgehog trundled along…” in teaching, and would very much like to use the stories for both teaching and language research purposes.

Many thanks!

LikeLike

I remember listening to Uncle Bill whilst stationed in Nienburg, as a Royal Engineer in the late 70s. My children were a little young to appreciate him, but at the time, there were no BFBS TV channels available in Nienburg, so I listened to much of BFBS radio output. I recall what was claimed to be the last episode ever, and Uncle Bill complained like hell at the end of his story about BFBS getting rid of him. I don’t know if this was a live show or a recording, but he did complain, most strongly.

LikeLike

Taught in RAF Bruggen in the 1970s and loved Big Wood. Most of the teachers did although I don’t know about the children!

LikeLike

The files are here:

https://onedrive.live.com/?authkey=%21ALr4icTRxjBOmI8&id=A45888D544D1F50D%21105461&cid=A45888D544D1F50D

LikeLike