Far from Britain being a nicer and more liberal society, the British invented racism. They built an empire in which racism was the organising principle. Nobody could have guessed that this black girl would have gone on to take her seat in the mother of parliaments, in the heart of the empire, in the heart of darkness, in the belly of the beast. – Diane Abbott, 1988 [1]

When she was asked by her tutor at Cambridge University what she wanted to do in life, Diane Abbott replied ‘Do good.’ [2] A couple of years later, as she successfully navigated the civil service entrance exams, she was asked by Mary Warnock, chairing the interview panel, why she wanted to be a civil servant, and she had a slightly different priority: ‘Because I want power.’ [3]

Perhaps her subsequent political career was an attempt to combine the two ambitions. And perhaps too it can be seen as having been a success. In 2008 the Observer drew up a list of the hundred most powerful black Britons, and there she was, keeping company with the Archbishop of York, novelist Zadie Smith and Baron Morris of Handsworth (Bill Morris, as was).

‘I hope I can exercise some influence,’ she commented. ‘Lists like this draw attention to people who are important and influential and positive role models in our community. We need to demonstrate that there’s more going on in the black community than football.’ [4] It was, then, a little unfortunate that her seventh-place ranking in the women’s section was matched in the men’s list by the footballer Rio Ferdinand.

Diane Julie Abbott was born in 1953 in Paddington, the oldest child of Reg and Julie Abbott, who had moved – separately – from Jamaica to Britain two years earlier. A sense of resolve and rebellion, she claimed, was in her blood: ‘When slavery was abolished, my people ran into the hills and made a living growing yam, coffee and sugar. My forebears refused to cut the sugar cane for plantation owners, and I am recognisably a product of that background.’ [5]

Reg had been an odd-job man in Jamaica, but now became a welder, while Julie – formerly a pupil teacher – retrained as a nurse. They did well enough that, when Diane was three and her brother Hugh was two, the family moved to the lower-middle-class suburb of Harrow, where they bought a house, in which rooms were let out: ‘Black families couldn’t get council houses in those days, so the only way up was to buy. It was only a little terrace house, nothing posh.’ [6]

The lesson Reg taught his daughter was simple: ‘In order to get on, you have to be not just as good as white people, but better.’ [7] And her chosen method of advancement came through literature. ‘I spent my childhood in a book,’ she recalled. Asked by a primary-school dinner-lady asked who her favourite author was, she had the precocity and the good taste to answer: H.H. Munro. This was not, though, the result of her home environment: ‘There were no books in our house. I lived my life in the public library.’ [8]

She attended Harrow County School for Girls, ‘a really old-fashioned girls’ grammar where you wore straw boaters in the summer and felt hats in the winter’. [9] She passed ten O-levels, even though her mother left home at the same time, and went on to get four A-levels, three with an A grade.

She was also in the drama society, where she met the likes of Michael Portillo, Clive Anderson and Geoffrey Perkins from the twinned boys’ school, though – despite appearing with Portillo in T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral – she says that she never starred in the productions: ‘I was one of those women wringing their hands in the chorus. It was obviously good practice for being a backbench woman MP under Tony Blair.’ [10]

She was the school’s star pupil, but even so, she says, her aspirations weren’t encouraged:

The school didn’t want me to try Cambridge. In fact, they were hostile. They thought I had ambitions above my station. I wanted to read history, and even the history mistress tried to talk me out of it. I’d got the idea of Cambridge from books, the sort I’d been hoovering up from the shelves since I’d been a child. That was where people in books had gone. I didn’t assume I would get in, but, it’s true, I did have ambitions far above my station. [11]

She passed the entrance exams and studied history at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she became aware for the first time of the reality of British class society. ‘There were girls on my corridor at college and they used to have sherry parties. They might as well have been conducting some bizarre social ritual,’ she recalled. ‘I can remember sitting next to a girl at dinner and listening to her talk about her family’s country cottage.’ [12] She was the only black British student from a state school at the university:

I remember going to a Cambridge May Ball as an undergraduate. I was dressed up in a long evening dress and made up and be-jewelled to within an inch of my life. Yet as soon as I came in through the gate someone rushed up to me and said, ‘Oh good, you must have come to do the washing up.’ He did not ask himself why I would wear an evening dress and diamante to do so. He only knew that I was a black woman and therefore must belong in the kitchen. [13]

Academically, it was difficult as well. Having been effortlessly top of her class at Harrow County, she now found herself struggling a little, emerging with only a 2:2 degree. ‘Maybe I peaked intellectually at 17,’ she reflected. [14]

But she also saw her time there as a life-shaping experience: ‘if you are working class and you go to Oxbridge, and you see one little corner of the British establishment strutting and resplendent, it can have the effect on you for the rest of your life of making you see a hurdle and be determined to clear it, whatever the odds.’ [15] She was – to use an expression that has since acquired different connotations – radicalized by Cambridge.

Having avoided the Cambridge Union (‘Ghastly place, full of ghastly people’ [16]) as a student, she joined the Labour Party soon after leaving university. She worked for a while at the Home Office, but rejected it: ‘I thought it could be transformed from within. I was wrong, I was just one token black person in a fundamentally racist institution.’ [17] So she left in 1978 and became a race relations officer at the National Council for Civil Liberties, which didn’t entirely impress her either: ‘It was the first time I’d met liberal do-gooders. I found them very patronising when it came to race issues.’ [18]

And so, in 1980, she moved into television as a researcher and sometimes reporter, first for Thames Television and subsequently for TV-am. At the latter company, she worked under Jonathan Aitken, the yet-to-be-disgraced Tory MP who would later become godparent to her son. And then, poacher turned gamekeeper: in 1985 she joined the Greater London Council (GLC) as a press officer.

By this stage, she had become a well-known figure on the London Left. In 1981 the annual conference of her union, the Association of Cinematograph Television and Allied Technicians (ACTT) rejected a call for an emergency debate on racism in the media, despite the fact that it was being staged just a couple of miles from riots on the streets of Brixton. As one of only two black delegates, Abbott found herself marginalized and patronized: when she ‘spoke to the rejected motion in another debate, her black unsmiling face received a splendid ovation. She had the dignity to leave in disgust.’ [19]

The following year, now being described as ‘a leading member of the Black Media Workers’ Association’, [20] she became the first black candidate to be elected onto the Conservative-dominated Westminster Council.

The great struggle of the time for Abbott and other black activists was the call for the Labour Party to institute racially segregated groups – black sections – within the party, based on the model of the existing women’s sections.

From early 1983 some constituencies, starting with Vauxhall and Lewisham East in London, began to set up such groups, though they lacked formal recognition. The movement grew with sufficient strength that it forced its way onto the agenda for the 1984 conference. In just eighteen months, Abbott said, it had ‘got the Labour Party establishment on the run’. [21]

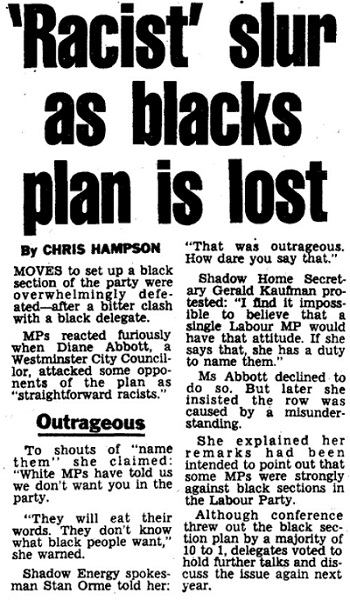

That sort of rhetoric didn’t go down well with the leadership. Nor did her 1984 conference speech; she got a hostile reception when she said that some of those opposing black sections were ‘straightforward racists’, and that this included senior figures: ‘White MPs have told us: we don’t want you in the party. They will eat their words. They don’t know what black people want.’ [22]

If many in the party were angry with the black activists, the hostility was amply reciprocated. ‘The Labour Party itself perpetuates racism,’ claimed a booklet produced by Vauxhall’s black section for the conference. ‘It is an institution rooted in a racist society and its own routine practices, customs and forms of organization exclude black people from the structures of power as effectively as if they were barred from membership.’ [23]

Under the still relatively new leadership of Neil Kinnock, this was the kind of dispute that the party didn’t really wish to have aired in public, and conference rejected the idea of recognizing black sections by 5.4 million votes to 0.5 million, as well as a proposal that five places on the national executive committee (NEC) should be reserved for black members. Abbott’s personal passage was also blocked: she stood for election to one of the five women’s places on the NEC and came eleventh in a field of twelve. (Those who were elected were Renee Short, Gwyneth Dunwoody, Betty Boothroyd, Joan Maynard and Ann Davis.)

The following year, Abbott and Lambeth councillor Sharon Atkin met Kinnock to press the case for black sections, but again found themselves rebuffed. He asked who would be eligible to join, and was told that the sections would be open to anyone who identified themselves as being black. ‘Can I consider myself black?’ he asked, and they replied: ‘Patently not, because you’re so obviously white.’ [24]

In fact, the movement had already passed its peak by this stage. In February 1985, Abbott had failed to convince even her own constituency party in Westminster North to support black sections. The best known member in the constituency, GLC leader Ken Livingstone, had fortuitously left the meeting before the vote was taken, thus avoiding the need to take sides.

At the time, Livingstone and Abbott were direct rivals, both seeking to win selection as the parliamentary candidate for Brent East, a safe Labour seat, where the incumbent, Reg Freeson, had achieved a majority of just under 5,000 even in the disaster of the 1983 election. Freeson, on the soft left of the party, had been targeted for deselection by the hard left for some time, and in April 1985 he was finally ousted. In the run-off ballot to choose a new candidate, Livingstone beat Abbott by 50 votes to 25, thus ensuring what was meant to be his triumphal transition to parliament and his inheritance of the leadership of the Left.

Abbott was also on an all-women shortlist in Westminster North, but ended up losing to Jenny Edwards. At the end of 1985, however, she got a much better offer, being selected as candidate for the safe East London seat of Hackney North and Stoke Newington.

She replaced – against his wishes – Ernie Roberts, who was, she said, ‘an excellent MP’, though he was also seventy-three years of age. [25] An old-fashioned militant, he’d been expelled from the Communist Party in his younger days for organizing too many strikes, and when he finally became an MP, at the age of sixty-seven, he seemed determined to make up for lost time; he demonstrated against Ronald Reagan and nuclear weapons, supported IRA prisoners and members of Militant, and argued in favour of reselection of MPs.

There was a certain irony, therefore, that, despite the backing of Livingstone and Labour Briefing, he himself then fell victim to the reselection process. He ‘complained bitterly about malpractices at the Hackney North selection conference’ [26] and presented his case in writing to the NEC, but failed to get the result overturned. Abbott had won, according to one witness, because: ‘She made the meeting laugh and her answers were by far the most impressive.’ [27]

Her selection, as the first black woman ever to be chosen to fight a safe seat, was a significant moment. She was named by the Daily Express as one of the political figures to watch for in the coming year, alongside Tory Chris Patten, John Edmonds of the GMB union, and Roy Lynk, leader of the Union of Democratic Mineworkers.

Moreover, her selection warranted a leader in The Times, though rather than congratulating her, the paper took the opportunity to denounce her ‘rhetoric of class struggle and skin-colour consciousness’. [28] Just nine months earlier, in the Brent East contest, the paper had described her as ‘Livingstone’s main soft left challenger’, [29] now it insisted that, although she wasn’t quite the same as Militant, she supplied a dash of Frantz Fanon to go in the Left’s ‘shared Leninist cocktail’. [30]

Despite Kinnock’s attempts to re-orientate the Labour Party, these were politically charged times, the era of the miners’ strike, of Derek Hatton’s Militant administration in Liverpool, of Ken Livingstone’s GLC and the ‘loony left’. The latter was where Abbott was deemed to fit in, primarily because she was black.

‘The whole thing about the attacks on the “loony left” was that they had a clear subtext of race,’ she was later to observe. ‘Whenever people talked about the loony left in London, they fastened on to me and on to Ken; and one of the “loony” things about Ken was that he spoke for black people.’ [31]

She was considered by many in the party to be a liability. It was notable, for example, that despite the extensive coverage she received elsewhere, the Labour-supporting Daily Mirror mentioned her in just three articles in the whole of the 1980s. The paper’s policy seemed to be one of pretending that she simply didn’t exist.

If any mainstream journalist was going to be sympathetic, it might have been Fiona Millar; born in Lambeth, educated at a Camden grammar school, and a future advisor to Cherie Blair and partner of Alastair Campbell, she had a c.v. that the tabloids would normally have considered perfect for the loony left. But, in a Daily Express article headlined ‘Black power struggle that is tearing Labour in two’, even Millar argued that ‘minority interest obsessions’ were ‘one of the chief reasons for disillusion with Labour’. This was a London problem, she argued, and Linda Bellos, Bernie Grant and Diane Abbott – who all happened to be black as well as Londoners – were ‘loathed by provincial MPs who have nothing in common with their extremist views’. [32]

But the attempts to ignore Abbott failed. And the attacks simply raised her profile still higher.

With the abolition of the GLC, she found a new – equally visible – job as the press officer for Lambeth Council, then led by Bellos. She began to be invited onto television, making her first appearance on Robin Day’s Question Time in June 1986, alongside Liberal Democrat Alan Watson, engineering union leader Bill Jordan (surely the prototype for Andy Burnham) and the yet-to-be-disgraced Tory novelist Jeffrey Archer. Later that year she was a guest of honour at the Women of the Year luncheon at the Savoy. Not the guest of honour, obviously – that was Princess Diana – and there were others listed above her: Kate Adie, Edna Healey, Toyah Willcox. But she was in there, even though she was still only a prospective parliamentary candidate.

And, it seemed, the prospect of soon becoming an MP might be causing her to tone down her positions. In May 1987 the black activist Sharon Atkin was removed as the candidate in Nottingham East for saying she ‘didn’t give a damn’ about the ‘racist’ Labour Party [33]; meanwhile four other veterans of the black sections movement – Bernie Grant, Paul Boateng, Russell Profitt and Abbott – were issuing a joint statement declaring loyalty to the party.

Nonetheless, she was still considered an extremist by many, not least by her rival Tory candidate in Hackney North, Oliver Letwin.

A member of Margaret Thatcher’s Policy Unit, Letwin was another Cambridge graduate, though one with whom she had little in common. For a man seeking to represent a constituency with such a high black population, he didn’t seem entirely committed to the cause of the inner cities. ‘Riots, criminality and social disintegration are caused solely by individual characters and attitudes,’ he wrote in a paper submitted to Thatcher, after the 1985 Broadwater Farm riot (and published thirty years later). ‘So long as bad moral attitudes remain, all efforts to improve the inner cities will founder.’ He was also dismissive of employment secretary Lord Young’s proposal to encourage new black entrepreneurs: ‘Young’s entrepreneurs will set up in the disco and drug trade.’ [34]

The personal attacks on Abbott started in a piece that Letwin wrote in The Times in 1986, quoting a document that he claimed she had written: ‘We are not interested in reforming the prevailing institutions of the police, armed services, judiciary and monarchy … We are about dismantling them and replacing them with our own machinery of class rule.’ [35]

In fact, the truth was both more prosaic and more interesting. The document, Alan Rusbridger had revealed the previous year, was a fake, taking some passages from an early draft of a discussion paper and adding ‘one or two monster raving loony Trotskyist inserts sufficiently extreme for the Labour Party powers-that-be to employ several barge poles in any future dealings with Ms Abbott’.

Who might have done such a thing? Some suspected the camp of Ken Livingstone, trying to scupper her chances of getting the Brent East nomination, but, noted Rusbridger: ‘Mr Livingstone resolutely refuses to comment on any of this.’ [36] Even though there was clearly no skulduggery on this occasion, the London Left did not always conduct its business in a comradely fashion.

Nor was the 1987 election campaign the most congenial of affairs. Abbott was now being described in The Times as ‘one of the new black extremists, far to the left of the already hard left Mr [Ernie] Roberts and a danger to democracy,’ while Letwin said she was ‘a revolutionary with no genuine allegiance to British parliamentary democracy’. Abbott retorted that he was simply playing the race card, but after all, she shrugged, ‘In a place like this, what other cards does an Old Etonian merchant banker have?’ [37]

Letwin also produced a leaflet alleging that ‘she gave a convicted IRA bomber a standing ovation and says that all white people are racist’. But, he insisted, none of this should be taken personally: ‘The leaflet is in no sense whatsoever an attack on Diane Abbott’s character, which I admire. It is an attack on her views.’ She wasn’t impressed and threatened to sue if he kept distributing copies. [38]

There was violence too. During the campaign, the Labour offices received a barrage of racial abuse by post and phone, and a brick was thrown through a window. This latter, however, might have been seen as retaliation after the Conservative office was burnt out in what was alleged at the time to be an arson attack.

The election results showed a national swing to Labour of around 2 per cent, but in London there was a contrary swing to the Conservatives of 0.5 per cent. Four of the leading campaigners for black sections became MPs: Bernie Grant in Tottenham, Paul Boateng in Brent South (‘Today Brent South, tomorrow Soweto,’ as he said in his victory speech), and Keith Vaz, who’d left London, in Leicester East. Abbott herself saw Labour’s majority reduced in Hackney North, though it still stood at a shade under 20 per cent, and the numbers voting for the party remained solid.

Even without Sharon Atkin and Russell Profitt (who failed to unseat Colin Moynihan in Lewisham East), it felt like a major moment in multiracial Britain. And the most significant win seemed to be that of Abbott, the first-ever black woman MP in Westminster.

A Times leader on the day after the election again opted not to congratulate her on her achievement, but instead cited her alongside George Galloway and Pat Wall (the latter a member of Militant) as ‘extremists, all powerful proponents of the unilateralist, anti-American policies which stand between the Labour Party and any prospect of a Labour government’. [39]

One thing that seemed certain, however, was that she was going to be a major political figure in the years to come.

In Part Two we follow Diane Abbott’s parliamentary and media career, culminating in her emergence as shadow health secretary under Jeremy Corbyn.

As with all the portraits in this series, this piece is drawn almost entirely from contemporary newspaper accounts. It is liable, therefore, to be wildly inaccurate.

ALSO AVAILABLE:

[1] Times 10 April 1988

[2] Sunday Times 1 December 1996

[3] Times 28 March 1992

[4] Observer 5 October 2008

[5] Daily Telegraph 17 June 2010

[6] Independent 18 January 1994

[7] Times 28 March 1992

[8] Independent 18 January 1994

[9] Observer 21 January 1996

[10] Guardian 19 December 1998

[11] Independent 18 January 1994

[12] Times 6 October 1990

[13] Times 17 April 1997

[14] Times 28 March 1992

[15] Times 6 October 1990

[16] Independent 18 January 1994

[17] Times 10 December 1985

[18] Independent 18 January 1994

[19] Guardian 15 April 1981

[20] Guardian 15 May 1982

[21] Times 1 October 1984

[22] Daily Mirror 4 October 1984

[23] Michael Leapman, Kinnock (Unwin Hyman, 1987) p. 74

[24] Times 14 June 1985

[25] Times 10 December 1985

[26] Guardian 6 February 1986

[27] Observer 15 December 1985

[28] Times 10 December 1985

[29] Times 9 March 1985

[30] Times 10 December 1985

[31] Times 6 October 1990

[32] Daily Express 9 April 1987

[33] Times 14 April 1987

[34] Daily Mirror 30 December 2015

[35] Times 3 June 1986

[36] Guardian 9 February 1985

[37] Times 18 May 1987

[38] Times 22 May 1987

[39] Times 12 June 1987

Anyone who wants to understand the attitude of Black British people in the 80s should read the story of the New Cross Fire in 1981. Thirteen teenagers died from a fire that was purposefully started and a traumatized survivor later committed suicide. The indifferent investigation by the police meant that it is unclear whether the fire was started by someone involved in a quarrel at the party or by a non-participant who was presumably racially motivated. (Other people may have firmer views). The tragedy was largely ignored by the press, by the Royal Family and by the political class. Soon afterwards, the Queen who had been unmoved by the death of 13 of her citizens was moved to send her condolences to the families of victims of a tragedy in the Republican of Ireland. When thousands of mainly black people marched in protest at the failure of the police to find the culprit and the indifference of just about everyone, the media focused exclusively on the criminal actions of a small number of the marchers. In short the story shows how the majority of white British people at that time saw their Black fellow citizens as essentially insentient beings worth no consideration or compassion. This was the environment in which the actions and motivations of Dianne Abbott and other black British politicians should be assessed.

Without wanting to pre-empt part II, it is interested to note how Grant, Abbott, Vaz and Boateng have fared. Abbott justified sending her son to a private school by claiming that black boys who go to comprehensives are likely to end up in gangs. Vaz has had a chequered personal and financial history that may now be emerging into public view. Like David Frost, Boateng has risen without trace, leaving only questions over his wife’s role in child services in Lambeth at a time of rampant abuse, over his wife’s behaviour when he was High Commissioner in South Africa and over his friendship with Lord Janner. Perhaps only the late Bernie Grant has emerged with his reputation intact, a man with the courage to state the obvious truth that police brutality would lead to brutality towards the police and with the ability to speak about slavery with a humour that meant that white people listened.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fair points, but I’d assume the Irish tragedy was a result of terrorism? (My knowledge of the period is sketchy especially as I wasn’t yet born.) By its nature, that type of incident raises more public sympathy and is deemed important enough for royal condolences – more so than what would be regarded as an accident, rightly or wrongly.

LikeLike

Fascinating article and highly readable as ever. The reduction in the Labour majority in Hackney North in 1987 is of note. Perhaps the seat still had a sizeable white British population in those days who were put off by Abbott. Stamford Hill is renowned for an Orthodox Jewish presence, and they lean Conservative. Letwin is Jewish. The big vote boost was for the Alliance though so maybe it was just an anti Abbott protest vote. I can’t think that the Alliance had a particular appeal there.

LikeLike

Black families couldn’t get council houses so the only way up was to buy!

The message is clear – If you make a personal effort instead of relying on the nanny state you will become a higher achiever.

LikeLike