In the summer of 2001, in the aftermath of yet another crushing election defeat for the Conservative Party, a member of the shadow cabinet came up with an idea about who to appoint as education spokesperson. ‘It would be a total punt,’ he admitted. ‘She is untested in a senior front-bench role, she knows nothing about education and has no profile. What about Theresa May?’1

It was intended as a joke, a snide comment on the perception that May was an inept politician. Because for the last two years, she had indeed been the party’s education spokesperson. And no one had noticed.

Theresa May was born in Eastbourne in 1956, the daughter of an Anglican clergyman, as Theresa Brazier. Her entry in Dod’s Parliamentary Companion (as Peter Hitchens noted on his blog in 20072) listed her ‘secondary schooling as “Educated at Wheatley Park Comprehensive School”.’ But that, Hitchens pointed out, wasn’t quite the whole truth: although it became a comprehensive during her time, the school was still a grammar when she first went there at the age of 13, and prior to that she had spent two years at a private Catholic school.

This must have been a simple oversight, however, for May is normally meticulous in such matters. When, for example, the Labour peer Baroness Jay was discovered in 2000 misdescribing her fee-paying alma mater, Blackheath High School, as ‘a pretty standard grammar school’, May was outraged: ‘She is the epitome of the hypocritical elite that is New Labour. She is trying to deceive the public.’3

May became involved in student politics at Oxford University, where she studied geography, a subject that is at least unusual in a front-line politician. She went on to work for the Bank of England and then to become head of European affairs at the Association for Payment Clearing Services. She was also, at the age of 29, elected to Merton Council.

In the 1992 general election, she stood for North West Durham, a safe Labour seat held by the future government chief whip, Hilary Armstrong. It was a token appearance, but she at least came second, beating a 21-year-old Liberal Democrat named Tim Farron, whose current whereabouts are unknown.

Undeterred by the defeat, she stood again, this time in the 1994 by-election in Barking, caused by the death of Jo Richardson. The Labour candidate was Margaret Hodge, whose controversial time as leader of Islington Council ensured that she got all the headlines. As for May: ‘the worst accusation levelled against her was that she was boring.’4

With John Major’s government plunging new depths of unpopularity, and Labour’s revival continuing despite the recent death of John Smith, the Tory vote in Barking collapsed from 34 per cent to 10 per cent, and May was beaten into third place by another 21-year-old Liberal Democrat, Garry White. Luckily there were four other parliamentary by-elections the same night, so no one noticed much, and May did her best to forget the humiliation.

Looking for a seat for the next general election, she failed to be selected for several constituencies, including Tewkesbury, Chatham & Aylesford and Ashford, before being selected to fight the newly created (but assumed to be safe) seat of Maidenhead. In the process she saw off the challenge of four sitting ministers who were seeking safe haven from the forthcoming storm – Paul Beresford, George Young, John Watts, Eric Forth – as well as the former chancellor, Norman Lamont, and a new hopeful, Philip Hammond.

At the time, there were precious few female candidates in the Conservative Party, where – in the words of the Billericay MP Teresa Gorman – women were largely seen as ‘nannies, grannies and fannies’.5 Those who did make it into Parliament tended to play down their gender. ‘I’m an MP who happens to be a woman,’ argued Ann Widdecombe, ‘in the same way that I’m an MP who happens to be short and fat.’6

A key part of the problem, it was generally accepted, was the women on the constituency selection panels. Even in the 1990s, in a post-Thatcher world, they were believed to prefer a youngish, good-looking professional man, with a wife who stayed at home looking after the children. Nonetheless, May got her chance eventually. ‘She will be one of the few career women to make it past the battleaxes on the selection committee,’ observed a man who was doing the same round of selection meetings; ‘that’s because she knows her recipes and doesn’t have children.’7

Similarly, Elizabeth Sibley who had stood for Durham North in 1992, was later to comment, ‘Theresa May and Eleanor Laing [MP for Epping Forest] had “male” backgrounds in terms of education, jobs and so on. The fact that they appeared to have made the decision not to have children also made them fit the stereotype.’8 (Just for the record, Sibley turned up again in this year’s election; now known as Liz St Clair-Legge, she garnered just 422 votes standing for the Northern Ireland Conservatives in East Londonderry.)

May herself brushed aside such calculations. ‘I’ve competed equally with men in my career, and I have been happy to do so in politics too,’ she insisted.9 In later years she would lead the campaign for the Tories to choose more female candidates, but at this stage, like Widdecombe, she had no intention of being typecast: ‘I have no burning ambition to promote women’s parliamentary rights,’ she said, shortly before the 1997 election.10

Nonetheless, the fact that she was one of just thirteen Tory women in the 1997 Parliament (twenty had been elected in 1992), and one of only five arriving for the first time, ensured that she stood out.

Indeed she had attracted some press coverage even when she was merely a candidate, though it was not always favourable. She marked her birthday in October 1996, noted The Times, with a ‘goo-goo press release’ that verged on ‘childishness’; it showed a photograph of her and Margaret Thatcher blowing out the candles on a birthday cake, accompanied by the caption ‘One big blow and together we’ll do it.’11 She was then forty years old. The same newspaper later wondered, ‘Is she the evolutionary consequence of the soundbite culture – devoid of irony, banal in the extreme, a robo-candidate?’12

Struggling to avoid controversy, she did nonetheless issue a statement during the election campaign saying that she would not vote for Britain to join the forthcoming single European currency. This went against stated party policy – John Major was trying to keep his options open – but it was not a particularly courageous move: well over a hundred candidates had already done the same, and many more were to follow. Despite Major’s caution, this was the new mainstream of the party.

The 1997 election was, of course, a complete catastrophe for the Conservative Party, driven out of office by the largest Labour landslide in history. May arrived just in time to spend thirteen long, miserable years on the opposition benches under a succession of five leaders.

The first of those leaders, however, was gone even before she got through the gates at Westminster. Major resigned on the morning after the election and the first decision the bedraggled band of Tories had to make was who should have the next swig from the poisoned chalice. (The leader was, at that time, chosen only by MPs.) May didn’t reveal who she voted for in the first ballot for the leadership – it was rumoured to have been Michael Howard – but in the second and third ballots she lined up behind the eventual winner, William Hague.

In the depleted parliamentary ranks, she attracted attention early on. By the summer of 1997, Andrew Pierce of The Times was identifying her as a ‘backbencher to watch’, along with Eleanor Laing, Nick St Aubyn and John Bercow, saying that she had ‘impressed the whip with her willingness to attack’.13 And by the end of the year the Independent on Sunday was tipping her for speedy promotion in Hague’s first reshuffle, describing her as ‘a comprehensive schoolgirl who made it to Oxford and is turning heads (politically speaking) at Westminster’.14 ‘When people talk about Teresa nowadays,’ bemoaned Teresa Gorman, ‘they mean my Conservative colleague, Theresa May.’15

In June 1998 she was given a job as schools spokesperson, serving under David Willetts, the shadow education and employment secretary. The Guardian sounded a rare note of caution, remarking that the Tories were ‘so desperate that they are giving frontbench jobs to people who have been in the House barely more than a year, the equivalent of the teenage boys Hitler sent into action towards the end of the war’.16

Most others were more enthusiastic. By the time of the Conservative conference in October 1998, with the Tories polling just 23 per cent, talk had turned to who might succeed Hague as leader. The top contenders were said to be Michael Portillo, Chris Patten, Iain Duncan Smith, Francis Maude and Liam Fox, but the Sun suggested that some were already thinking of May ‘as a wild card’. Then again, the Sun wasn’t the most reliable source of information: it also described her as ‘a former teacher’. Which she wasn’t.17

More realistically, a leader column in the Independent in January 1999 called for her to be promoted into the shadow cabinet, saying that she was ‘reasonable, measured and televisual’.18 And that June she was duly bumped up to take over from Willetts as the party’s senior spokesperson on education and employment. (The Independent’s leader on this occasion predicted she would prove to be ‘measured, reasonable and televisual’ – having decided on its soundbite, the paper was clearly reluctant to let it go.19)

She had been in the Commons for barely two years, and her rapid rise was almost entirely explained by the paucity of talent available to Hague. Education was, after all, a sensitive policy area that Tony Blair had claimed as his top priority. (Or rather as all three of his top priorities, in one of his more fatuous soundbites.) May was perfectly alright on television and in the House, but she hadn’t really done anything to warrant such advancement. It was by no means clear that she was capable of shadowing such a major department of state.

To her credit, she tried to make an impact. She delivered speeches advocating ‘free schools’, to be set up by groups of parents, and ‘partner schools’, in which private companies would be encouraged to invest their money and expertise. She suggested that a Tory government would permit schools to select by academic ability, allowing them to become new grammars. And she promised to ‘set universities free’, though no one was very clear quite what this meant.

At the Tory conference in 2000 she called for trainee teachers to spend 80 per cent of their time in schools, for the reintroduction of the assisted places scheme, for head teachers to be given greater powers to expel pupils, and (again) for more grammar schools. She also argued that teachers accused of abusing pupils should be given anonymity unless and until they were found to be guilty. And she opposed the repeal of Section 28.

Whether any of these were good ideas, they were at least something. The Conservatives were producing policy initiatives. It’s just that no one was listening. Even the teaching unions – seldom reticent when given the chance to denounce any suggestion of change – struggled to summon up the enthusiasm to condemn her proposals. (In fact, she sometimes found herself on the same side, as when a Labour idea to allow 16-year-olds to buy alcohol in pubs ‘sparked anger among teachers and Tories’.20)

If anyone had wished to hear more, she would soon have dissuaded them. There was a plodding pedestrianism to her performance that kept interest at bay. She was, for example, gifted the open goal of a story about Margaret Hodge (by now the schools minister) helping to launch a booklet titled ‘Towards a Non-Violent Society’, which, among other things, warned that the game of musical chairs was bad for children’s health. The best May could manage in response was: ‘This is political correctness gone mad. Musical chairs is a popular children’s game that has been played and enjoyed over the years.’21

As the conference season started in 2000, the Daily Express showed photographs of various politicians to ten members of the public in Brighton, asking them if they could identify the people pictured. None could name May, though to be fair, she wasn’t alone in her anonymity: Iain Duncan Smith, Liam Fox and David Willetts also went unidentified.22

By then there were already reports that Hague had intervened to take over schools policy for himself, ‘after growing unease at the low profile of shadow education secretary Theresa May.’23 Her lack of public profile was lambasted everywhere. ‘We have not heard a squeak from her,’ complained Michael Brown in the Independent.24 ‘Who remembers anything said by Theresa May?’ asked the Guardian.25 Peter Oborne, while counter-intuitively (as is his wont) praising the quality of Hague’s shadow cabinet, admitted that she was an exception: ‘Among cabinet ministers only David Blunkett easily outshines his shadow, Theresa May.’26 Jon Craig, political editor of the Sunday Express, rounded off 2000 by giving Hague some New Year’s advice: ‘Dump your spokeswoman Theresa May, who is useless.’27

Senior Tories were said to agree, having concluded that she ‘has been drastically over-promoted and will have to be moved before the general election campaign.’ One colleague was quoted as saying: ‘William will come under pressure to move her to a less high profile portfolio. She has not laid a glove on David Blunkett.’28

Theresa/Teresa

Another unnamed ‘senior Tory’ added: ‘The only time she got any publicity was when she was confused with a porn star.’29 The reference was to the British glamour model Teresa May, and briefly the association worked in Theresa’s favour: at least there was now some way of remembering who she was. (Nobody was really confused, of course, but it was a good story and Theresa took care to mention Teresa in interviews.)

Despite all of which, May remained in her post into and beyond the 2001 election, seemingly unscathed by the barrage of criticism. Her own result attracted further sniping. ‘She took a majority of 12,000 and turned it into 3,000,’ a colleague sneered to the papers. ‘That takes hard work. You don’t do that in a weekend.’30 It was a poor performance; turnout was down everywhere that year, but even so, her majority collapsed from 24 to 8 per cent. It has, though, since recovered and this year she recorded a massive 29,000 (54 per cent) majority.

The continuing travails of the Tories at the ballot-box ensured that Hague was obliged to stand down, and in the ensuing contest May pledged her support for Michael Portillo to be his successor. Portillo was the modernising candidate and it was assumed that the party would decide to adapt to the new political realities of a socially liberal Britain. But under new rules for electing the leader, MPs got to choose two candidates, who would then be voted on by all the party members, and Portillo – who had alienated many of his colleagues with his apparent arrogance – failed to make the cut.

It now seemed likely that the party would opt for Iain Duncan Smith, thereby retreating further into itself, despite having suffered two disastrous defeats in a row. Faced with this prospect, several of the Portillistas wrote to the Daily Telegraph saying that only ‘radical change’ would give the Tories the chance ever to win again:

We need to change the way we think, the way we sound and the way we behave… We have both to feel and show genuine passion and interest in the manifest problems of Britain’s health, education and transport systems… Unless people, especially younger people, see us as a party that has something serious to say and to do about the lives that they live today, rather than the lives we think they ought to live, they will not vote for us.31

May was amongst the signatories, along with Francis Maude, Damian Green, Stephen Dorrell, Peter Lilley and others. It had no immediate effect. Duncan Smith was chosen to be the new leader and the attempt at a major overhaul was put off until another trouncing at the polls made it imperative.

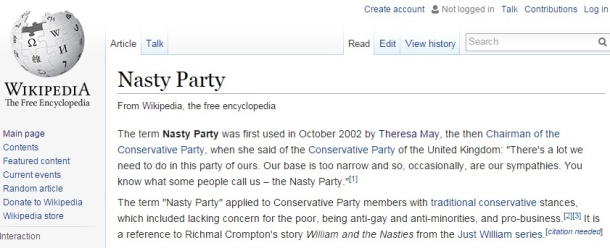

May’s best-known contribution to the modernising project – indeed her best-known contribution to politics at all – came at the 2002 Conservative conference, which she addressed in her capacity as chairwoman of the party. ‘You know what they call us?’ she asked the faithful, as they snoozed gently in Bournemouth. ‘The nasty party.’32 And that phrase made her political career. She was ‘the Iron Lady Mark II’, proclaimed the Sun.33

According to Wikipedia, she was the first to use the expression ‘nasty party’, but that is far from the truth. It had been used to describe the Tories by Simon Jenkins in The Times as far back as 199534 when John Major was leader, and it had returned with William Hague, one ‘senior Tory MP’ referring to ‘the skinhead Tory party, the nasty party, not a respectable alternative party of government’.35 By 2001 the phrase was so common in political discussion that even William Rees-Mogg was using it.36 And in an interview in February 2002, Duncan Smith said he understood the sentiment: ‘Asked if the Conservatives are still regarded as the “nasty party”, he agrees. “I do. I think too often it is the case that people fall back on the sense this is the party that doesn’t chime with them because it seems to know about all the things it dislikes.”’37 In fact there were dozens of instances in the year or so leading up to the 2002 conference, including from May herself.

Contra Wikipedia, Theresa May was not the first to bemoan the ‘nasty party’, but her critique was the most memorable.

So why did it attach itself to her in particular? Partly it was the timing. Duncan Smith’s leadership was coming under heavy fire: his colleagues were suggesting that his initials stood for ‘In Deep Shit’,38 and the same colleagues would go on to sack him the following year. Some thought that May was launching a further attack on him, but that was unfair; he was persuaded of her case, even if he was never going to be the one to sell it to the electorate. Nonetheless the speech was clearly a blunt demand for a very different kind of party to replace what was starting to look like ‘an absurd sect’.39

‘Yes, we’ve made progress, but let’s not kid ourselves,’ she said. ‘There’s a way to go before we can return to government. Our base is too narrow and so, occasionally, are our sympathies.’40 And, she pointed out, in words that seem almost as relevant today: ‘Twice we went to the country unchanged, unrepentant, just plain unattractive. And twice we got slaughtered.’41

That was really why the speech made such an immediate impact. It was actually very good indeed. It was also the complete antithesis to a normal chairman’s speech, an occasion that was traditionally used to rally the troops, not to tell them that they were a bunch of racist, sexist, homophobic reactionaries who needed to buck their ideas up and get with the program.

‘Theresa May flagellated the party. She scourged them and lashed them and they loved it,’ said The Times. ‘She was immediately being discussed as “the next leader”.’42 The paper also noted her footwear. She ‘wore ‘leopard-print “hot to trot” kitten heels from Russell & Bromley (£110)’ for the occasion; henceforth the phrase ‘kitten heels’ was to be attached to her name for years.

As to why the speech still lingers, why it is better remembered than anything else in May’s career – that’s because it’s the best thing she’s done. She went on over the next eight years to shadow various portfolios: she did transport, local government, the family, culture, women and equality, work and pensions and spent a little time as shadow leader of the house. But she remained as nondescript as she had been in education and employment. Not anonymous anymore – the nasty party and the kitten heels had seen to that – but definitely nondescript.

Put her on television, on Question Time or the like, and she was absolutely fine. She could talk well, she didn’t get flustered, she seemed like a perfectly nice person. She also said not a single word that was memorable, expressed not an idea that was surprising. She seemed competent, but really very dull. Hard, perhaps, to believe this of a geography graduate who went on to become a banker, but such things do sometimes happen.

When the Conservatives – now in the hands of the modernisers – finally won a general election (well, almost) in 2010, David Cameron appointed her home secretary, where she has remained ever since. She’s been in the job longer than anyone since R.A. Butler more than fifty years ago – and she’s only a month shy of overtaking him. Indeed, there’s no reason to suppose she won’t still be there next summer to break James Chuter Ede’s post-war record. In a quiet way, it’s a remarkable achievement: the home office isn’t traditionally an easy place to work, and for every Roy Jenkins or Michael Howard, who enhanced their reputations there, there’s always a David Waddington or a Leon Brittan.

And the reason it’s such a difficult job is that there’s always something going wrong. There are administrative failures, difficult deportations, fights with the Police Federation (May’s quite good at these), scares about terrorists and paedophiles, disputes over drug classifications and a thousand other problems. And then there’s immigration. In May’s time as home secretary there have been many moments of crisis, but somehow she has sailed serenely on. There have been periodic demands for her resignation, which she has simply ignored. ‘Home secretary Theresa May was fighting for her political life last night,’ read the papers back in 201143; yet she’s still in the same job.

She has been helped by having Yvette Cooper as her opposite number for several years, because Cooper was a useless shadow home secretary. But mostly her survival is down to the fact that she has a boss who doesn’t panic and that she’s been quite competent. For a Conservative home secretary, she’s been reasonably liberal (more so than her Labour predecessors), so she doesn’t attract leftist hostility like other leading Tories; meanwhile Conservative loyalists see her as being somehow in their own image, but not overly inspiring.

Even her choices on Desert Island Discs seemed designed not to give offence: Elgar, Abba, a decent hymn and a recording of Yes Minister. Her chosen book was Pride and Prejudice. And, to make sure that there was some coverage beyond the blandness, she went for the Four Seasons classic, ‘Walk Like a Man’ – vaguely suggestive of something, but nothing in particular.

As a politician, she seems so incorporeal. It’s as though there’s nothing solid there on which one could land a punch. For two decades, she has avoided controversy, showed no particular commitment, refused to grab anyone’s attention. The one exception came with that speech in 2002. But then, having kicked out and stirred up the waters, she simply clambered back onto her lily pad and looked placidly on. ‘If she is eventually forced to resign,’ Martin Ivens once wrote in the Sunday Times, ‘a terrible truth will dawn. How will anyone notice she’s gone?’44

And yet, she’s still seen as a likely entrant in the race to succeed David Cameron as leader. George Osborne and Boris Johnson may be bigger names, but May is definitely in with a chance as the compromise candidate. And if the party has a torrid time over Europe in the next couple of years, compromise may well be an attractive offer.

Whether she would be successful as a leader is uncertain. But there’s always the possibility that she’s better than she appears to be, that the longevity is evidence of her tenacity and strength of character. Perhaps she really is the Iron Lady Mark II. If so, she sometimes ventures into territory where the original never trod. ‘Women used to fake orgasms and make mince pies,’ she said in 2005. ‘Now we can do the orgasms – but we fake the mince pies.’45 Margaret Thatcher would never have faked a mince pie.

As with all the portraits in this series, this piece is drawn almost entirely from contemporary newspaper accounts. It is liable, therefore, to be wildly inaccurate.

ALSO AVAILABLE:

Diane Abbott

1 Sunday Express 15 July 2001

2 http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/2007/05/lessons_in_gram_1.html

3 News of the World 4 June 2000

4 Times 10 November 1995

5 Times 29 December 1995

6 Nicholas Kochan, Ann Widdecombe: Right from the Beginning (Politico’s, 2000) p. 209

7 Times 10 November 1995

8 Times 23 November 1998

9 Guardian 10 November 1995

10 Times 22 April 1997

11 Times 20 November 1996

12 Times 1 February 1997

13 Times 31 July 1997

14 Independent on Sunday 28 December 1997

15 Express 18 December 1997

16 Guardian 9 June 1998

17 Sun 8 October 1998

18 Independent 27 January 1999

19 Independent 16 June 1999

20 Daily Mirror 4 October 1999

21 Daily Mirror 24 May 2000

22 Daily Express 1 September 2000

23 Daily Express 22 May 2000

24 Independent 28 August 2000

25 Guardian 16 June 2000

26 Sunday Express 25 February 2001

27 Sunday Express 31 December 2000

28 Daily Express 31 August 2000

29 Daily Mirror 31 August 2000

30 Sunday Express 15 July 2001

31 Daily Telegraph 10 August 2001

32 Daily Telegraph 8 October 2002

33 Sun 8 October 2002

34 Times 28 June 1995

35 Sunday Times 24 September 2000

36 Times 3 September 2001

37 Scotsman 1 February 2002

38 Daily Record 11 October 2002

39 Daily Telegraph 8 October 2002

40 Guardian 8 October 2002

41 Daily Telegraph 8 October 2002

42 Times 8 October 2002

43 Sun 9 November 2011

44 Sunday Times 13 November 2011

45 Daily Telegraph 18 June 2005

Even the orgasms and mince pies quip wasn’t actually original; she borrowed it from the fictional character Kate Reddy, from Allison Pearson’s “I Don’t Know How She Does It” (2002). (There’s a contemporary LA Times review which quotes it.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: ‘Politics is not like shopping’: A press profile of Hilary Benn | Lion & Unicorn

Pingback: The next prime minister | Lion & Unicorn

Pingback: ‘They wouldn’t put up with those hats’ | Lion & Unicorn

Pingback: Tomorrow belongs to May | Lion & Unicorn

Pingback: After the Plausible Young Men | Lion & Unicorn

Pingback: Plausibly mature? | Lion & Unicorn

Events, dear boy, events.

Corbyn next…

LikeLike