I go and see a movie show

People move when I come near

But when I’m standing on that stage

People shout for more and they cheer.

– The Chants, ‘Man Without a Face’ (1968)

The death on 23 February 2018 has been announced of Eddie Amoo. He sang with the Chants and then the Real Thing, and he was one of British music’s greatest figures. I had the pleasure of speaking with him in 1996, and these are some of his words…

The Beatles

There was a big venue called the Tower Ballroom, and we went over to see Little Richard, and the Beatles were on the bill. We got talking to them, and they invited us to come down to the Cavern when they returned from Hamburg and audition for them. They couldn’t really get their heads round the fact that we were a vocal group who just sang and didn’t play.

So we went down to a lunchtime session and waited for them to finish, and then we approached them. By this time the place had emptied out and Paul said, ‘Okay well get up there, see what you can do.’ The four of them were standing at the back of the Cavern eating hamburgers when we got up on stage, and I’ll always remember the look on their faces when we started singing – they all came running down to the front, and Paul said, ‘Look you gotta come down here tonight and do a show with us. We’ll back you. We’ll get off a little spot now.’ And that was it. Right there, we got off four songs, and we went out that same night. We did ‘Sixteen Candles’, ‘Duke of Earl’, ‘A Thousand Stars’ and the other one I can’t remember.

The Cavern was the first public appearance of the Chants, and it was with the Beatles – the Beatles backed us. What we did was we came in half–way through their show, and they introduced us to the audience. That was the beginning of the Chants’ career.

The Chants

Basically, what happened with the Chants was that the record companies had no idea what to do with a black doo–wop group, they just had no idea. A black band in England needs a lot of work, needs a lot of dedication if they’re gonna be successful.

I remember there was Clem Curtis and the Foundations and they had a lot of hits. But basically they used to record them type of bands like white bands. If you turned on the radio and you heard an Equals record or a Clem Curtis and the Foundations record, you’d think you were listening to a white pop band. Eddy Grant didn’t really develop his real serious music identity until quite a while after the Equals, and then he really came into his own. But in that era, the late ’60s, very early ’70s, most black bands in this country that were recorded were recorded like white bands, and they sounded like white bands. They used to record the Chants like a white pop band, which we weren’t. But we weren’t musically adept enough in those days to establish what we really wanted ourselves – we weren’t musicians then.

‘Man Without a Face’ (1968) was a good record for its time. And very heavy, as well. That was one of my songs, and it was the forerunner to a lot of the stuff that I started to write with the Real Thing – sort of a message thing. But it was written in, what, 1964-65? So it was way, way ahead of its time. When I think back, I’m amazed we got it released. That was probably the Chants’ best single.

Towards the end of the Chants’ career, we did make one really good record called ‘I’ve Been Trying’ (1976), which has now become a classic. It didn’t happen, but it was a good record, and it could have happened if it’d been promoted properly, you know.

What the Chants lacked and what the Real Thing had was Tony Hall. Tony Hall is an astute manager with an astute track record in the business, and basically he knew what needed to be done to break the Real Thing. The Chants never had anybody like that – we were just like a ship drifting about, one port to another, never quite landing. But the Real Thing landed.

The Real Thing

They were called Vocal Perfection; they changed their name the night before they were due to do Opportunity Knocks to the Real Thing. They were driving through Piccadilly and Tony Hall, seeing the Coca–Cola advert, said, ‘That’s what you’re going to be called: the Real Thing.’

The Real Thing started out with three people, then went to five, then they dropped two out and by 1975 they’d become a trio – Ray [Lake], Dave [Smith] and Chris [Amoo, Eddy’s younger brother]. But by then Chris and I had started to write together. I was still with the Chants, but I was writing for the Real Thing, because the Chants were no longer a vehicle for the songs I was writing – the Chants were doing cabaret, and the Real Thing were able to play these songs live, so I was writing and giving the songs to Chris.

I wrote ‘Vicious Circle’ (1972), then ‘Plastic Man’ (1972), which almost made it, and then a song called ‘Daddy Dear’ (1974), and they’re all heavy songs – if you listen to them lyrically, they’re all really heavy. And the other one that I wrote was called ‘Listen, Joe McGintoo’ (1973); really it was called ‘Civil War’, but our manager made me change the lyric and the title of the song, but basically it was about Ireland. They weren’t soul records, but they weren’t rock records – they were somewhere inbetween. I think the best way you could put it is they were too original, too different for the mainstream.

Now around about this time the record company said: ‘Look, you guys have got to have a hit, you’ve got to give us something we can sell.’ And that’s how come we recorded ‘Stone Cold Love Affair’ (1975).

The original plan when I joined the Real Thing in 1976 was to branch out into something else and get a girl singer and change our name and come at it from a completely different angle. And then all of a sudden we took off.

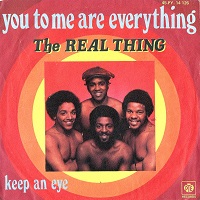

‘You to Me Are Everything’

We met up with this guy called Ken Gold, who’d been trying to flog ‘You to Me Are Everything’ all over London and been knocked back all over the place. And when we heard it, we thought: this is a quasi–Barry White song, this’ll keep them off our backs. What happened with Ken was for the first time we worked with somebody who didn’t just allow us to throw our voices on the way we wanted to. He wanted it done in a certain way, which caused a little bit of friction in the studio, but it worked.

By this time I think we’d given up all hope. After a while you don’t even think about having a hit – you just get on with it.

For a British soul group to have a hit in England in the ’70s, it had to be a quasi–soul record. It had to sound like a soul record but have a very, very strong pop overtone – i.e. ‘You to Me Are Everything’ (1976).

There’s a few reasons the Real Thing got lucky – David Essex was one of them.

Jeff Wayne had a jingles company. He used to use the Real Thing on a lot of his jingles, so he liked our voices. This was before I joined the band, but he came to see the band play, brought David Essex to see the band play and that’s how the relationship began. I’ll always be heavily indebted to Dave ’cos there was no need for him to do it – he could have done what everyone else did, sorted out three or four white guys to come in and do his backing vocals. But he admired our vocals, he really genuinely liked our sound.

David Essex introduced the Real Thing through the back door to a big white audience. And basically that was instrumental in us being successful. We did Olympia, we did Earls Court – we did Earls Court as ‘You to Me Are Everything’ was released: you couldn’t ask for a better start. We were doing two numbers of our own and doing his backing vocals. So we were on stage a long time, being seen.

Sooner or later a serious black group had to come along and break through, a serious black group that was sellable to a huge white audience. And we were just lucky to be at the right place at the right time.

Our first album (Real Thing, 1976) was all our songs, but all the songs had been written basically maybe five or six years before. And as soon as ‘You To Me’ took off, we went right into the studio and recorded them all.

‘You to Me Are Everything’, ‘Can’t Get by Without You’ (1976), ‘You’ll Never Know What You’re Missing’ (1976), ‘Love’s Such a Wonderful Thing’ (1977) – they were all sort of aimed completely at radio. They did happen in the clubs, but they were aimed at radio. Which was how everyone was going and making records then.

We had a little glitch where ‘Lightning Strikes’ (1977), which was the fourth single, didn’t happen, so basically we brought Ken Gold back. And we recorded another one of his songs called ‘Whenever You Want My Love’ (1978), which was successful. And that was the end of the relationship with Ken.

Missed opportunities

What happened with ‘Let’s Go Disco’ (1978) was this – let’s get this straight. Our manager rang us up and said, ‘Biddu would like you to do this song which is going to be in this film called The Stud.’ Right away, as soon as we heard the name Biddu, we went: no. ’Cos musically we’re like light years apart. But then the record company came on and said, ‘This song’s going to be in The Stud, we’re going to get worldwide promotion on the song.’ In the end, after a lot of pressure, we thought: okay. But then the record company went further and demanded that the song be released as a single. We’ve never performed it live on stage. That is the record we’re least proud of.

The Real Thing did all the vocals on The War of the Worlds [1978] originally, did the whole album. Pye wouldn’t agree a deal with Jeff [Wayne], so they had to wipe all our vocals off. And it became one of the biggest selling albums of that time. We were heartbroken, heartbroken. ’Cos that would have given us the credibility we wanted.

The funny thing is that one of our most successful songs with the Real Thing was ‘Children of the Ghetto’, which has never been a hit, but has been on a lot of big albums. It’s just been in Clockers (1995), the Spike Lee movie. It was a co-written thing with me and my brother Chris, while I was with the Chants – must have been in 1974 – but we could never use it, because basically we didn’t really have that type of audience to use it for. So therefore the Real Thing got it.

In 1978 we completely re-wrote it ‘coz we thought, this song’s dying, and it’s too good a song to let go. And it found its way to Phil Collins, who did it with Philip Bailey on the Chinese Wall album (1984). And from that album, there was no stopping it. Courtney Pine picked it up and did it on his album Journey to the Urge Within (1986). And then it’s been picked up by so many bands across the world – it’s just totally mad. And yet we’ve never been able to get a record company to release our version – ’cos we rewrote the song, and we’ve never been able to get anybody to release the rewritten version.

If, for instance, we’d released ‘Children of the Ghetto’ and had a hit with that, I think our career would have taken off in a completely different direction, it would have gone in the direction we wanted it to go in. But who’s to say whether that would ever have happened?