SIMON MATTHEWS revisits Todd Haynes’s 1998 movie Velvet Goldmine.

The great cliché is that if you remember the 1960s you weren’t really there. Well, plenty of people seem to remember the ’70s despite being about five years old at the time, a prime example of this vicarious enjoyment of recycled memories being Velvet Goldmine.

Premiered in May 1998 at the Cannes Film Festival (where it won a Special Jury Prize for Best Artistic Contribution), its plot will be familiar to anyone who has seen Citizen Kane: a journalist (Arthur Stuart) is piecing together the life of an enigmatic celebrity (Brian Slade) and interviewing those who knew him. For reasons that aren’t clear, it is set in 1984 and Slade is a former glam rock star who faked his murder on stage ten years earlier (i.e. in 1974).

Much of it is set in the early ’70s and shown in flashback. It follows Slade, who is clearly modelled on David Bowie, during his ascent in the music industry, and explores his relationship with US rock star Curt Wild, an Iggy Pop/Lou Reed composite. All kinds of other characters are worked in as well who may (or may not) be modelled on people who were around then.

Starting with the positives. The costumes are fine (and got the film nominated for an Academy Award), the general ambience of the period is more or less captured and the acting is terrific. Jonathan Rhys Meyers is impressive as Slade/Bowie, Christian Bale is good as Stuart and Ewan MacGregor a force of nature as Wild/Pop-Reed. Neither Meyers or Bale were born when the events portrayed took – or would have taken – place, and McGregor would have been about three years old, so it is a tribute to them that they carry off their roles with such aplomb. Adding ballast, and further down the cast are Eddie Izzard (born 1962, so in the first flush of adolescence then) and Lindsay Kemp, who had an affair with Bowie back in 1968-1969, as an elderly pantomime dame.

The problems arise with the approach taken by director Todd Haynes, who also wrote the script. Noted for exploring gay and LGBT issues, his intention here was clearly to re-imagine the glam-rock era, focussing specifically on Bowie’s career. (The film’s title comes from an obscure Bowie B-side, recorded in 1971 and eventually released in 1975). Trying to get actors to play characters who were still alive – and not that old either, only in their fifties at that point – clearly presented difficulties and led to them being on the one hand fictionalised, whilst still recognisable as the real-life stars, with the audience playing a guessing game about their identity.

The objects of this veneration were unimpressed, particularly Bowie who disliked the script saying ‘When I saw the film I thought the best thing about it was the gay scenes. They were the only successful part of the film, frankly.’ Which was not surprising. By the late ’90s he had no interest in going retro and was attempting to reinvent himself, working with Goldie and dipping a toe into the drum and bass scene. Claiming he would be making his own film about the ’70s (he didn’t), he declined access to his songs.

Which turned out not to be quite as disastrous as he may have wished. After all, 1998 was the Brit Pop era with bands happily recycling the riffs of 25 years earlier to produce perfectly curated new releases. The soundtrack – which included originals by Reed, Roxy Music, Brian Eno, Steve Harley and T Rex – piggy-backed on this by featuring Teenage Fanclub, Placebo and Pulp as well as a couple of contemporary US acts mining the same seam. Showing considerable ingenuity, to get around the absence of most of the music identified with glam, two new bands were formed for the film: The Venus in Furs with Andy MacKay (Roxy Music), Bernard Butler (Suede), Jonny Greenwood and Thom Yorke (both Radiohead) to do Bowie-type approximations and The Wylde Ratttz, with former Stooge Ron Asheton, performing Iggy Pop songs. Both work well.

It appears the film lost money on release, but may have broken even by now, via DVD sales, streaming and TV repeats. Is it any good? Reviews ranged from cautious and guarded to outright praise. But that’s scarcely the point. The bigger question must be why ‘re-imagine’ the past? An exercise of this type will be neither fiction nor history and likely to confuse with the events portrayed freighted with a significance that may have been completely absent at the time.

Particularly when glam-rock was such a niche sub-genre of the wider scene and lasted for such a brief period. Bowie had abandoned it by 1974 at the latest (after Diamond Dogs), the classic Roxy Music line-up was gone by the end of 1973, Lou Reed’s album sales began tailing away at the same time and Iggy Pop didn’t achieve commercial traction until the end of the decade. The New York Dolls – not referred to in the film – stuttered along for five or six years shedding personnel without achieving any significant sales.

What Haynes provides instead is a comforting look back to past icons for contemporary folk exploring gender and queerness. In doing so, he creates for them a world they would recognize today, but wasn’t necessarily recognizable then – rather like the ‘hipster’ recreation of Victorian London in the 2017 film of Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem.

The film is worth watching, but the soundtrack album (on vinyl, of course) is better.

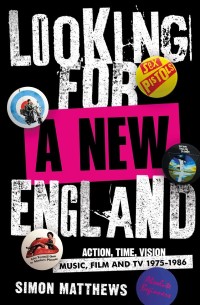

from the maker of:

see also: