It was now the turn of the consumers to learn the strike lesson – the most powerful class of all, but the most heterogeneous to weld together.

Ernest Bramah, The Secret of the League, 1909We hope it will have a very wide effect indeed on the minds which have not yet perceived the speed of the downward rush towards ‘insecurity’.

The Spectator on The Secret of the League, 1909

The Representation of the People Act 1918 was one of the defining pieces of legislation in modern Britain, giving the vote to all men over the age of twenty-one, and – with a property requirement – to women over thirty. In the general election that year, 18.9 million people were registered to vote, up from 7.9 million in the previous poll.

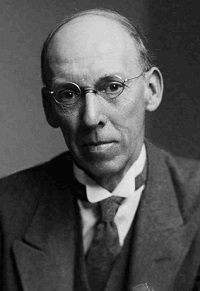

What would be the effect of such an extension of the franchise? One person who had given this some thought was Ernest Bramah, whose novel What Might Have Been was published by John Murray in 1907, predicting that future elections would be determined by ‘a class which, while educated to the extent of a little reading and a little writing, was practically illiterate in thought, in experience, and in discrimination’.

The book attracted little attention and sold poorly, but it did have its admirers, including, presumably, someone at the publishers Thomas Nelson, who suggested an abridged version for their budget ninepence series. (It’d be nice if it were John Buchan, working for Nelson at the time, who bought it up.)

The result was The Secret of the League, published in 1909 and an edited version of What Might Have Been (though it still weighed in at a substantial 94,000 words). In the new format it proved very popular, though not so much these days.

By coincidence, the near-future time-frame culminates in 1918, the year of that transformative Act. In Bramah’s narrative, Britain’s first Labour government has already been and gone by this point, replaced by a Socialist administration, who are themselves now looking nervously to their left, to ‘the extreme Socialists’ with their ‘revolutionary and anarchical wing’. Even that may not be the end, because there’s always the danger that a yet more extreme new party might rise:

A party composed of paupers, aliens, chronic unemployed, criminals, lunatics, unfortunates, the hysterical and degenerate of every kind, together with so many of the working classes as might be attracted by the glamour of a final and universal spoliation, led by a sincere and impassioned firebrand.

The process has been constitutional, but the changes have been revolutionary. The House of Lords has been abolished, the Church’s land has been seized, Ireland has declared independence, and the Empire is largely dismantled: many of the Colonies, have ‘dropped off into the troubled waters of weak independence’, while the others ‘clung on with pathetic loyalty’ despite ‘the disintegration of all mutual interests’.

It hardly needs saying of the government that ‘the word “patriotic” had long been expunged from their vocabulary’. The armed forces have been run down because ‘the Labour Party was definitely pledged to the inauguration of universal peace by declining to go to war on any provocation’. Consequently, when there are rumours of a foreign invasion, everyone assumes – ‘in view of the sweeping reductions in the army and navy’ – that such an invasion will be successful.

Cabinet government has virtually ceased to exist, replaced by a smaller Expediency Council, and although it’s not a police state, the Amalgamated Union of Policemen and Plain Clothes Detectives is definitely behind the government. Officers are armed, wear no number or other identifying mark – since that would be demeaning – and are distinctly hostile to the middle class.

And then there have been the economic changes. ‘The Labour and the Socialist administrations proved superlatively extravagant’ and the bills for their programme of bread and circuses have to be paid somehow. So there’s been a big increase in income tax, a new charge on the employment of servants, a cap on share dividends, and the threatened introduction of the Personal Property Tax: ‘For the first time in history, property – money, merchandise, personal belongings – was to be saddled with an annual tax apart from, and in addition to, the tax it paid on the incomes derived from it.’

It seems there’s little further to go: ‘So highly taxed was every luxury now that the least fraction added to its burden resulted in an actually decreased revenue from that source.’ But the need for further advance remains, because the working class, ‘having found by experience that they only had to ask often enough and loudly enough to be met in their demands, were already clamouring for more’. Among the current proposals are workers on boards of companies and a minimum wage or, better yet, ’a full and undocked living wage to every worker in or out of work’.

And yet, despite all the changes, is the lot of the working man really any better? ‘There was a great deal of money being spent on him, and for him, and by him, but he never had any in his pocket. And the working man’s wife was even worse off.’

That’s the backdrop. The story is of the middle-class fightback in the form of the Unity League.

The League is headed by the evocatively named Sir John Hampden, and masterminded by George Salt, a naval hero possessed of the same spirit that drove Drake, Hawkins, Greville and Blake, ‘the Elizabethan spirit – the genius of ensuring everything that was possible, and then throwing into the scale a splendid belief in much that seemed impossible’. Their political platform can be ‘summed up in the single phrase, “As in 1905”.’ A re-setting of the clock, to a time before the extension of the franchise, when there was still a Conservative government.

For two years, the League quietly builds its numbers – some five million people sign up – and plans its campaign. And in the summer of 1918 it launches a boycott of the single most significant sector of the economy; it calls on its supporters not to buy any coal, nor use gas or electricity that is produced by coal. As a substitute, the League has been busily stockpiling imported oil for its members.

The impact on the working class is devastating. Hundreds of thousands of miners are laid off but such is the position of coal that it’s not just they who are affected, but also the railway-workers and the dockers, the stokers and gasworkers, the carters, stablemen and canal workers, not to mention the chimney-sweeps and carpet-beaters. As a government minister admits: ‘There is not a trade in England, from steeple-building to hop-picking, that will not be a little worse off.’

And so the stage is set for class war.

It’s a fabulous book, sometimes thriller, sometimes satire, always political.

Well, nearly always political. Being set a decade into the future, it also includes some nice science-fiction touches: personal wings have been developed that enable people to fly (it’s a bit like swimming, apparently, though it requires more practice), and there are neat designs for a code-machine and a fax machine.

But mostly it’s political. And though Bramah’s sympathies are very clearly with the Unity League, he’s wide-ranging in his condemnation of ‘Conservative ineptitude, Radical pusillanimity, Labour selfishness, and Socialistic tyranny’. He’s also perfectly clear-sighted in his references to ‘the days when politics were more or less the pastime of the rich, and the working classes neither understood nor cared to understand them – only understood that whatever else happened nothing ever came their way’.

What really makes it, though, is the quality of the writing. Bramah had written humorous pieces before – he’d worked as Jerome K. Jerome’s secretary – and he has that characteristically British humorist’s love of parodying language that is convoluted, mealy-mouthed or otherwise risible.

Here’s Comrade Tintwistle of the railwaymen’s union, pre-empting Private Eye’s Dave Spart by seven decades, as he denounces the way that ‘the insatiable birds of prey who sucked their blood laughed in their sleeve at the spectacle of the British working men hiding their heads ostrich-like in the shifting quicksand of a fool’s paradise’. And here’s the British government responding to Irish independence, informing ‘the new republic that its actions were not what his Majesty’s Ministers had expected of it, and that they would certainly reserve the right of taking the matter in hand at some future time more suitable to themselves’.

Equally characteristic of the British humorist are the names he gives to the Labour politicians: Strummery, Guppling, Cadman, Heape, Pennefarthing, Vossit, Chadwing, Stub, Bilch.

On the other side of the class divide is John Hampden’s nephew, the languidly Honourable Frederick Tantroy. He’s infatuated with a music hall artist, billed as ‘The World’s Greatest Inverted Cantatrice’, who ‘hangs by her toes to a slack wire eighty-five feet above the stage and sings: “Things are strangely upside down, dear boys. Nowadays.”’

Freddy Tantroy’s finest moment is his description of the intrepid heroine of the piece, Irene Lisle: ‘Hockey girl, I should imagine. Face of the pomegranate type, carved by amateur whose hand slipped when he was doing the mouth.’ And that inspired turn of phrase runs through the book. A police inspector is ‘a powerfully-built man with “uniform” branded on every limb, although he wore plain clothes’. Or how about this summary of Japan, a nation with a ‘cheerful smile that is so mild in peace, so terrible in war’.

Bramah would later turn his hand to crime fiction (he created the blind detective Max Carrados) and there’s some spy sub-plotting that hints in this direction. He also wrote uncanny tales, and there’s a fearsomely atmospheric scene as John Hampden sits alone with a dying man in a slum room near Drury Lane. ‘There was something in the situation that was more than gruesome, something that was peculiarly unnerving.’ In a related vein, there are some disturbing images; as a particularly bitter winter sets in and real poverty and lawlessness descends on the cities, strange behaviour is observed:

To add to the terror of the night there suddenly sprang into prominence the bands of ‘Running Madmen’ who swept through the streets like fallen leaves in an autumn gale. Barefooted, gaunt, and wildly dressed in rags, they broke upon the astonished wayfarer’s sight, and passed out again into the gloom before he could ask himself what strange manner of men they were. Never alone, seldom exceeding a score in any band, they ran keenly as though with some purposeful end in view, for the most part silently, but now and then startling the quiet night with an inarticulate wail or a cry of woe or lamentation, but they turned from street to street in aimless intricacy, and sought no definite goal. They were never seen by day, and whence they came or where they had their homes none could say, but the steady increase in the number of their bands showed that they were undoubtedly the victims of a contagious mania such as those that have appeared in the past from time to time.

And some of it is just beautiful writing in the turn-of-the-century style that I love so very much:

At one end of the thoroughfare a milkman was going from area to area with a prolonged melancholy cry more suggestive of Stoke Poges churchyard than of any other spot on earth; at the opposite end a grocer’s errand boy, with basket resourcefully inverted upon his head, had sunk down by the railings to sip the nectar from a few more pages of Iroquois Ike’s Last Hope; or, The Phantom Cow-Puncher’s Bride.

If I’m quoting too much, it’s because I’m worried you won’t immediately go and read this wonderful book. And you should, you know, you really should. If you’ve got this far, you’ll love it.

So, one more lengthy quote… As the socialist government looks as though surely it must crumble, its one serious figure, Tirrel (the one with a sensible name), is plunged into despair. But he rouses himself sufficiently to issue a defiant warning to Sir John Hampden that, whatever setbacks are encountered, the victory of socialism is assured:

You will not see it; I may not see it, but it is more likely that the hand of Time itself should fail than that the ideals to which we cling should cease to draw men on. We, who are the earliest pioneers of that untrodden path, have made many mistakes; we are paying for them now; but we have learned. Some of our mistakes have brought want and suffering to thousands of your class, but for hundreds of years your mistakes have been bringing starvation and misery to millions of our class … our reign will come again; and when the star of a new and purified Socialism arises once more on a prepared and receptive world the very forces of nature would not be strong enough to arrest its triumphant course.

It’s powerful, stirring stuff, mercilessly undercut by Bramah’s next lines:

‘Hear! hear!’ said Mr Vossit perfunctorily, as he looked round solicitously for his hat. ‘Well, I suppose we may as well be going.’

see also: