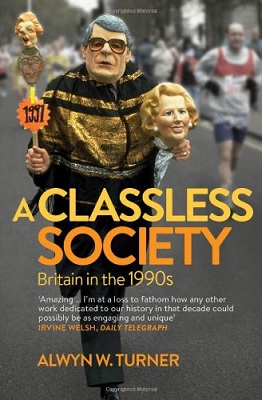

John Redwood has announced that he won’t be standing in the general election, so here’s an extract from Alwyn Turner’s A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s.

It’s 1995, a long-running Conservative government is exhausted and riven by splits. With rumours of a leadership challenge, the prime minister John Major announced that he was standing down as leader and putting himself up for re-election. The intention was to force Michael Portillo’s hand, but Portillo refused to play. So in his absence, who would step forward to challenge Major…

The answer was John Redwood, who had come into the cabinet as secretary of state for Wales in the reshuffle following the departure of Norman Lamont, and who was being described in the press as ‘the cabinet’s most junior member and its resident rightwing rottweiler’. In his memoirs, John Major hinted that Redwood acted because ‘he had heard gossip that there was a sporting chance that he might not survive the reshuffle planned for July’, but that was ungenerous. Redwood was a politician of deep conviction and principle, and his decision to resign from the cabinet to put himself up for the leadership took real political guts. Though little known to the public, he was still only forty-four, he had an ultra-safe constituency and he could confidently look forward to more senior posts in government.

He was, however, lacking the aura of leadership, to an even greater extent than Major. Having catapulted himself into the headlines, he now came under serious media scrutiny for the first time, and he never really recovered from the footage that was discovered of him on a platform in his early days as Welsh secretary trying to mime to ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’, the Welsh national anthem, with hilarious ineptitude. His head wobbled, his face seemed petrified into vacancy and he managed to look both feeble-minded and patronising, like an Oxford don reading a storybook to a primary-school class. But that was just a single incident, albeit one re-broadcast frequently over the period of the leadership election. The real problems came when he actually spoke. Because, although no one ever really defined it, something wasn’t quite right about Redwood’s public persona.

He was self-evidently the most constructive and gifted thinker in Major’s cabinet, the one Tory working to develop new policies that could extend the Thatcherite revolution without being enslaved to her memory. His track record was impressive; he had been one of the first to advocate privatisation of state assets, long before Margaret Thatcher herself espoused the concept, but he had later argued with her against the introduction of the poll tax.

He also had a keen understanding of the aspirations of first-generation suburban families. This was the same constituency to whom Major made his pitch, but the difference between the two men was instructive: in place of Major’s apparent empathy, there was a remoteness to Redwood, a lack of warmth, an inability to communicate a sense that politics was anything more than a cerebral conundrum.

This perception was unfortunate and unfair, for Redwood was certainly a practical politician, not an abstract intellectual, but it proved impossible to shake. And it was most commonly associated with Matthew Parris’s description of him as resembling Mr Spock from Star Trek. In fact Parris did not restrict his characterisation to Redwood alone; the conceit, spread over several political sketches in The Times from 1989 onwards, was that the Conservative Party was being taken over by members of the Vulcan tendency, ‘infiltrators from a strange and distant planet’ who were ‘courteous, clever and ruthlessly logical’. Included in their ranks were Francis Maude, Peter Lilley, David Curry, Alan Howarth and Michael Portillo as well as Redwood, while in 1994 Parris revealed that the military strategists on Vulcan had now refined their design and that Tony Blair was ‘an improved version, with added charm’. It was only with Redwood, however, that the tag stuck, seeming to capture something of the awkwardness of the man.

In terms of other politicians, he was most often compared to Keith Joseph, the self-flagellating prophet of Thatcherism in the 1970s, and to Enoch Powell in his romantic reverence for the nation. But there was also an element of Tony Benn: polite, calm, uncontaminated by scandal (‘John has never been exposed to germs,’ according to a colleague) and absolutely convinced that what he was saying was blindingly obvious common sense. ‘The key to Redwood was that he had very simple views expressed in a subtle and original manner,’ wrote his adviser, Hywel Williams. ‘Hence a view of the history of England that was not so far removed from the stories of the Boys’ Own Bumper Book of History.’

When interviewed on television, Redwood exhibited a strange half-smile, suggestive of a private joke at the audience’s expense and, although those who knew him insisted he was a witty man, his attempts at humour in public mostly displayed a clumsy jocularity. He once said that he’d like to be Mr Blobby – ‘He’s nice and everyone likes him’ – but if comparison with a children’s television character was sought, then rather more accurate was Gyles Brandreth’s suggestion of Daddy Woodentop.

Major claimed in retrospect that Redwood was the ideal opponent – ‘beatable, Eurosceptic and a cabinet colleague’ – but it seems unlikely that at the time, with Portillo refusing to break cover, he was expecting such a heavyweight challenge. For despite his obvious limitations as a communicator, Redwood was a serious candidate, with a plausible alternative vision of where the Conservative Party should be heading. This was not simply a stalking-horse campaign, preparing the way for others, but the action of a man who had ideas above his station as Welsh secretary, even if these had hitherto been confined to dreams of the chancellorship. To the surprise of many, he turned out to be a fighter, and the fact that he was prepared to resign from the cabinet to battle for his beliefs won him some grudging respect.

Redwood’s cause did go on to attract a handful of serious players, including Norman Tebbit and Iain Duncan Smith, one of the more highly regarded of the new intake of MPs, but it was the campaign launch that shaped much of the coverage that was to come. Recognisable faces alongside the candidate were in short supply – the only major figure was Lamont – and the rest looked a distinctly unimpressive crowd, dominated by Teresa Gorman in characteristically overstated outfit (a shoulder-padded, puff-sleeved jacket in vivid green, worn over a turquoise blouse) and by Tony Marlow, the man who had the previous year demanded Major’s resignation in the House of Commons and had recently called him ‘a nice guy, but a loser’.

Remarkably, Marlow’s outfit overshadowed even that of Gorman, a striped blazer that, thought Major, ‘would have looked good on a cricket field in the 1890s’. In fact it was the official blazer of the Old Wellingtonian Society, reflecting the fact that, unlike Major, he was a public schoolboy. In an early indication of sympathy for Redwood’s challenge, the Daily Telegraph delicately cropped the photo of the launch to exclude Marlow.

available in paperback