The last years of Cromwellian rule and the early years of the Restoration of the monarchy after 1660 were deeply troubled times. A substantial part of the population still believed that the monarch was divinely appointed and that the state-ordained execution of Charles I in 1649 had therefore been a crime against God Himself, while even those who supported the regicide were increasingly disillusioned by Cromwell’s imposition of military rule.

It was a period of chaos and confusion, marked by disturbances in the natural and social order; a time when strange tales abounded. And none were stranger than the disappearance of William Harrison of Chipping Campden – what became known as the Campden Wonder.

Chipping Campden is a small Gloucestershire town in the Cotswold Hills some twelve miles south of Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1660 it comprised a single street and was dominated by the ruins of Campden House, largely burnt out during the Civil War to prevent it falling into rebel hands. The owner of this house – though she did not live there herself – was the Viscountess Campden, and William Harrison was her steward.

Harrison was then seventy years old and had served the Campden family for half a century. He was a married man and lived with his wife, his son Edward and a servant named John Perry in a part of Campden House that had escaped the blaze.

Two incidents preceded the disappearance of William Harrison that may or may not be related to the mystery.

First, in 1659 there was a robbery at Harrison’s quarters. While the family was at church one day, a ladder was placed against the house, a second-storey window was broken into and £140 of Lady Campden’s money was stolen. The burglar was not apprehended.

Then, a few weeks later, the servant John Perry was heard crying out for assistance in the garden. When help arrived, he was found alone but in a state of some agitation. He claimed that, while working in the garden, he had been unaccountably set upon by two men dressed in white, who had assaulted him with their swords. He had, he said, driven them off with the assistance of the sheep-pick he had with him. He showed this implement which was reportedly hacked about the handle, as though it had indeed been struck by a sword. No other report of the ‘men in white’ was ever given.

These unexplained incidents form the prelude to the main event, which took place on 16 August 1660. On the morning of that day William Harrison set off on foot to the neighbouring village of Charingworth, to collect rent from tenants of Viscountess Campden. Some time after eight o’clock in the evening, he having not returned, his wife sent John Perry out to look for him.

Neither master nor servant came back that night, and on the following morning William’s son Edward went out to find either or both. He met Perry on the road, and the two of them proceeded to Ebrington, a village between Campden and Charingworth, where it was reported that William Harrison had called in the previous evening on his way home. This was the last sighting of the old man.

Later that day, however, a woman reported that she had found a hat, a comb and a neckband at the roadside not half a mile from Harrison’s home. Upon hearing of this discovery, the villagers all embarked on a search for what was now expected to be the corpse of William Harrison. It was not found.

A local Justice of the Peace, Sir Thomas Overbury, was called upon to make preliminary investigations, and his description of the items that were discovered by the roadside sets the tone for the mystery that was to develop: ‘The hat and comb being hacked and cut, and the band bloody, but nothing more could be found.’

There was no blood on the hat or comb – suggesting that they had not been on Harrison’s head when they were ‘hacked and cut’ – nor was there any blood on the road. The band worn around Harrison’s neck, on the other hand, was bloodstained. It wasn’t entirely clear what these facts meant, but certainly foul play was now assumed.

The most immediate suspect was John Perry. He was promptly arrested and asked about his movements after he had been sent out to look for his master.

He stated that, being afraid of the dark, he had made little initial progress, and had in fact spent at least an hour sheltering in a hen-house until, sometime around midnight, the moon had risen and made his task easier. He had then, however, got lost in a mist and had ended up sleeping by the roadside. On waking he had begun to make his way back home, at which point he had been met by Edward Harrison. A couple of villagers provided independent corroboration of his account up to perhaps ten o’clock; thereafter his word stood alone.

For a week, John Perry was held in detention at the local inn, where he speculated ceaselessly on the disappearance. And then, seemingly of his own volition, he confessed all to Sir Thomas Overbury.

Perry confessed that he, his mother Joan and his brother Richard Perry had between them murdered William Harrison, for the purpose of stealing the rents the old man had collected that day. They had followed Harrison home, strangled him and intended to dump the body in a nearby waste-pool. Whether this was done or not John Perry did not know, since his part of the clear-up operation was to leave the hat, comb and band by the roadside, presumably to divert attention.

Going back to the incidents of the previous year, he added that it was his brother who had robbed the house (with his, John Perry’s, connivance) and that the story of the ‘men in white’ who had attacked him in the garden was a complete lie.

It was an intriguing, if perplexing, story that raised more questions than it answered.

Both Joan and Richard Perry totally denied the tale, and it conflicted with the statements made by the two villagers who had each seen John Perry on the night in question. Furthermore the description of the supposed murder weapon – a rope with a slip knot – failed to account for the bloodstains found on William Harrison’s neckband. And Harrison’s body was not found in the waste-pond, nor anywhere else.

Most intriguing of all was why John Perry chose to bring up the earlier incidents, particularly that of the ‘men in white’, which had no apparent bearing whatsoever on the present case.

Despite the incoherence of his account, John Perry, his mother and his brother were charged with both the robbery and the murder and were brought to trial in September 1660. They were advised to plead ‘guilty’ to the charge of robbery – somewhat foolishly, since the Act of Pardon and Oblivion passed by Charles II on his Restoration would have ensured that they would have received an amnesty; but there is no reason why we should believe in this plea – there was no evidence against them save for John Perry’s confession – and indeed they subsequently withdrew their admission of guilt.

The murder charge, however, was not heard on this occasion, on the grounds that no body had been found and therefore there was no evidence that William Harrison had really been killed. The three were held in jail (where John Perry claimed that his mother and brother tried to poison him) until the following spring, when the case – complete with the charge of murder – was brought before another court.

All three now pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the killing of Harrison, with John Perry insisting that his confession was invalid since ‘he was then mad and knew not what he said’. It was the first sensible statement he had made in the course of the investigation, but it came too late and all three were convicted and sentenced to death.

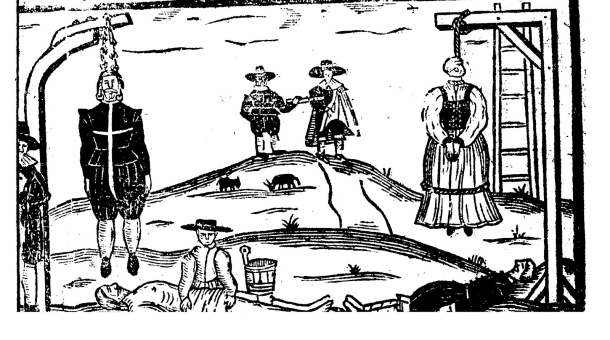

Joan Perry was popularly supposed to be a witch, and was therefore hanged first, in the belief that she had maybe cast a spell on her two sons and in the hope that, with her death, they might come to their senses. They did not, and both Richard and John Perry were also hanged. The latter declared on the scaffold that ‘he knew nothing of his master’s death, nor what has become of him, but they might hereafter (possibly) hear’.

It was a confusing case in which a scant provision of evidence was supplemented by prejudice, madness and supposition. All that can be said without fear of doubt is that John, Joan and Richard Perry were the victims of a miscarriage of justice. Almost certainly they did not commit the robbery in 1659, and there is absolutely no possibility that they killed William Harrison.

This latter statement can be made with such certainty for one simple reason. A couple of years after the events described here, William Harrison returned to Chipping Campden, very much alive.

The resurrection of a murder victim is not an everyday occurrence and naturally much interest was expressed in what really happened that night in August 1660. What Harrison had to say, however, cast only further shade over an already murky episode.

In a written statement to Sir Thomas Overbury, Harrison stated that on that fateful day he had gone to collect rents but had been delayed by the fact that it was harvest time and all the tenants were out in the fields. Night was therefore falling by the time he had made his way homeward. Near Ebrington, he said, ‘there met me one horseman who said “Art thou there?”’

Riding straight at him, the horseman stabbed him in the side with a sword. Two other men then appeared, one of whom stabbed him again, this time in the thigh. They seized Harrison, handcuffed him, put him up on one of the horses, and rode off.

Later that night, they took the twenty-three pounds of rent money he had collected and ‘tumbled me down a stone-pit’. They appear then to have had second thoughts, for an hour later they came back, dragged him out of the pit, wounded him a third time, stuffed ‘a great quantity of money’ in his pockets and rode off with him. Two and a half days of riding ensued until this strange, small band came to Deal in Kent. There Harrison was put aboard a ship.

For six weeks, Harrison was confined on this ship. ‘Then the Master of the ship came and told me, and the rest who were in the same condition, that he had discovered three Turkish ships.’

The human cargo – there is no indication of how many others ‘were in the same condition’ – was passed over to these ships, and the captives were eventually deposited near Smyrna (now known as Izmir) in Turkey. What happened to the others is unclear, but Harrison was sold to a Turkish doctor, who was eighty-seven years old and who claimed to have once practised in Lincolnshire.

Harrison remained enslaved to this elderly physician until the latter’s death, working in the cotton fields and mixing chemicals for him. He then made his own way to the nearest port, where he traded a silver-gilt bowl – given to him earlier by the physician – for a passage to Lisbon. There he met an Englishman (again, coincidentally, from Lincolnshire) who brought him back to Dover.

At this stage, one begins to look back upon John Perry as a paragon of sanity. For the entire story told by Harrison is riddled with unanswered questions.

Why would slavers bother with a seventy-year-old man? Why wound him thrice and thus damage the goods? How did a wound to his side and another to his thigh manage to stain his neckband with blood but leave no trace on the road?

Why take him to Deal, 160 miles away, rather than nearby Bristol, a much busier port where it would have been easier to cover one’s tracks? How did the three men manage to carry a handcuffed prisoner across half of England without question?

How come no other disappearances were reported that might account for the other human cargo of the ship? What kind of slave trader is it who just sails around waiting for a chance encounter with some Turkish ships to sell his goods?

Where was this Lincolnshire man who arranged the passage from Lisbon to Dover? And why did Harrison endure being enslaved to an eighty-seven-year-old for what must have been a period of around two years?

All these questions, and more, went unanswered in William Harrison’s account.

There are no more facts to reveal. Nothing else is known. So let us try to grope toward the truth of this story.

First of all, we have to rule out John Perry’s confession. He subsequently withdrew it and anyway the fact that William Harrison was not in fact murdered invalidates the whole story.

Second, we can discount Harrison’s own version of events. It is literally incredible, it lacks any kind of corroboration and it conflicts with what little evidence is known to exist, principally the bloodstained neckband.

If Harrison was indeed abducted, then who could benefit from his disappearance? Only perhaps his son, Edward Harrison, who took over as steward to Lady Campden’s estate. But if he were so anxious to obtain the post that he was prepared to have his own father kidnapped, why not have the old man killed and be done with it? That would at least preclude the possibility of his presumably unwelcome reappearance. In any event, such a plot by Edward Harrison can hardly account for the sudden madness and confession of John Perry, nor the wild and fanciful tales of his father.

A theory that William Harrison was suffering from amnesia similarly fails to fit the facts. It would not explain the bloodstained neckband and it would not explain John Perry’s behaviour, even supposing that one could accept Harrison wandering a countryside where he was well-known without being discovered.

And if Harrison staged his own disappearance, why is it that he ‘left behind him a considerable sum of his Lady’s money in his house’? Furthermore, his known movements that evening, when he was certainly returning home and was within half a mile of his own house, do not easily fit with a premeditated departure.

A more convincing theory was proposed by Andrew Lang, writing about the case in the Cornhill Magazine in 1904. He proposed that Harrison’s disappearance was political and related to the Restoration of the monarchy. Harrison and his family were Puritans and it is possible, Lang suggests, that the old man simply knew too much about something from the dark days of the Cromwellian terror. He was therefore spirited away and kept in hiding for two or three years while the fuss died down. The hat, comb and band were placed at the roadside as a deliberate false trail, and the subsequent absurd story concocted to conceal the facts. ‘By an amazing coincidence,’ Lang adds, ‘his servant, John Perry, went more or less mad.’

This, however, is surely where Lang’s theory falls somewhere short of satisfactory. He writes that ‘such mad self-accusations as that of John Perry are not uncommon,’ which may well be true, but seldom are they so fortuitous. It is possible to accept that some powerful men were able to persuade Harrison to hide out for a while, but they cannot have anticipated that someone would confess to his murder.

And Perry did so of his own volition, remember; he was not tortured into making the confession. The ‘amazing coincidence’ is surely a little too amazing. Lang fails too to make allowance for the events of 1659, save to deduce that Perry was perhaps already mad and that the burglary was unrelated.

Leaving theory behind for a moment, let’s recap the bare facts of the case. In 1659 John Perry reported being assaulted by two unknown ‘men in white’. The following year, two very strange things happen on the same night in a small, remote village: one man goes completely mad, and another – ‘a man of sober life and conversation’ – vanishes entirely, only to return a couple of years later, also bewildered by delusion and unable satisfactorily to account for his time away. He too tells tales of mysterious assailants.

If this was a story from anytime in the last fifty years, there would be only one obvious explanation: alien abduction. Only the fact that it occurred three centuries before the first published account of such an abduction has prevented it from becoming part of the literature.

This account is based on the version published in Andrew Lang’s Historical Mysteries (Smith, Elder, 1904). A fuller account of the Campden Mystery can be found here.

see also: