I haven’t read many of the stories about Sexton Blake, detective and action-adventure hero. Mostly, that’s because the sheer volume of them is so daunting: the very wonderful Blakiana website has a bibliography stretching to 5,000 items, and although that includes serial episodes and collections, it’s still an awful lot of material.

And, frankly, some of it is simply awful. As Blakiana also notes, ‘more than two hundred authors wrote Blake tales,’ from Hal Meredith in 1893 – the first story appeared in the same week that Sherlock Holmes was lost in the Reichenbach Falls – through unknown hacks to the likes of John Creasey and Michael Moorcock, with new adventures appearing well into the Swinging Sixties and beyond. In this mad rush of writing, quality control was not always adhered to.

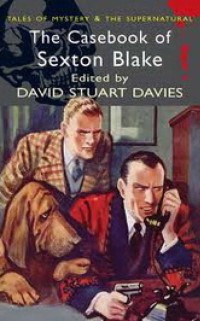

There are good stories in there; it’s just that a reader needs some guidance to sort the wheat from the chaff. Which is where a volume such as The Casebook of Sexton Blake (Wordsworth Editions, 2009) is so invaluable. It collects seven of the best early tales, dating from 1907–1923, comprising over 200,000 words, and they’re all very strong. No match for the really great detective fiction, perhaps, but securely in the second league: fast-paced page-turners that are still entertaining.

Actually, they’re not really detective fiction so much as thrillers. Sexton Blake wasn’t big on sleuthing and deducing, and in his Golden Age between the wars, he would become the British precursor to Batman, fighting a series of increasingly implausible supervillains: Doctor Satira, Mr Mist, Miss Death, Waldo the Wonder Man, Zenith the Albino and many, many more.

Mark Hodder, who runs the Blakiana site (really, I do recommend it), contributes a good introduction to the Wordsworth book, which traces the publishing history, and observes that with the passing of time, the tales have acquired an additional value, as ‘a fascinating source of social history’. He’s right. The sheer speed at which these were churned out – three or four episodes a week at the peak of production – means that they depict the attitudes and assumptions of the outside world rather well.

As a cultural historian with a fondness for thrilling tales of adventure, I find this stuff irresistible. And then I read the following, tucked away on a left-hand page at the end of the Introduction:

Publisher’s note:

While some of the views expressed in this book, particularly on racial issues, are regarded as unacceptable today, it is important that the reader should bear in mind that the stories reflect the attitudes of their times. However, even after taking this factor into consideration, we have amended certain words that we feel would give particular offence.

That annoys me deeply. Apart from anything else, the offensive stuff is exactly what I was looking for and why I bought the book. The Casebook of Sexton Blake includes ‘The Brotherhood of the Yellow Beetle’ (1913), in which Prince Wu Ling leads a conspiracy that’s sworn to fight ‘until the white races, who have in their vanity spurned us and oppressed us, are under the heel of the East’. There’s more than a hint here of Sax Rohmer’s Chinese supervillain Fu Manchu, who had made his debut the previous year, and that interests me.

Because, having recently re-read the first Fu Manchu book, I wanted to explore the depiction of China in the popular culture of pre-World War I Britain, and Sexton Blake seemed like a valuable part of the picture. But not if I can’t trust that the words I’m reading are actually from the period. That renders it entirely useless as social history.

More than this, Wordsworth’s censoring of Sexton Blake should be seen as an early manifestation of the current trend for rewriting the classics. (Remember that this is 2009; a year later Wordsworth collected John Buchan’s Richard Hannay yarns and felt obliged to warn us in the blurb that Hannay held ‘some of the racial prejudices of his day’.)

There’s been much attention in recent months about the vandalism being perpetrated on the work of Roald Dahl and – may God forgive the publishing industry – PG Wodehouse. But that’s not where this absurd revisionism started. First they came for Bram Stoker, Enid Blyton and Sexton Blake, and no one much cared because this wasn’t serious literature. So we let them get away with it, only to discover that, like one of those animals – so common in adventure fiction – that can never be trusted once they’ve tasted human flesh, publishers have acquired a taste for strong meat.

And now, here we are. The spirit of Thomas Bowdler is once more stalking the land. Except that that’s not fair on Bowdler. When he and his sister, Harriet (who was uncredited, but did much of the work), published The Family Shakespeare (1807), removing all the offensive stuff, the Edinburgh Review argued that this should be accepted as the standard version of the plays: ‘It is better in every way that what cannot be spoken, and ought not to have been written, should now cease to be printed.’ But Bowdler, to his credit, disagreed: ‘It was the young people and the modest innocence of the female members of the household that were to be protected against the full impact of Shakespeare.’ The original work, he believed, should be allowed to stand. And, indeed, it did stand; it survived while the Bowdlerised version was forgotten.

This will also be true of Dahl and Wodehouse, because they’re too big to be silenced. It’s the likes of Sexton Blake who will disappear in their original form. And I think that’s a shame. Enough of this pathetic attempt to protect us from the prejudices of the past. And anyway, who the hell is this supposed reader who wants to consume over 500 pages of pulp adventures from a century back, but who is also going to be distressed by the language of the time? Absolute nonsense.

see also: