Whether Lee Anderson ‘well represents the laboratory-engineered toxicity of the Sunak era’ or is the tribune of a working class ‘excluded and stigmatised’ ‘ by the ‘radically progressive consensus’, the former coalminer and Labour councillor has perhaps made the biggest public impact of the 140 non-incumbents elected as MPs in 2019.

But while Anderson is a self-described New Conservative, there is something awfully familiar about his commitment to almost self-parodic plain-speaking. In fact, the archetype probably had its heyday about the time Anderson’s father was a striking miner, and when the Tory prime minister was even less likely to deploy the f-bomb in public than the current one.

Margaret Thatcher’s political ascendancy was in part based on votes from a section of the working class attracted by her creed of self-reliance and sceptical of the metropolitan liberal attitudes she scorned, and while neither she nor John Major (from even more humble roots) were given to Anderson-esque outbursts, other colleagues were not so abashed. Teddy Taylor, Geoffrey Dickens and Teresa Gorman were as proud of their modest roots and outspoken even to the point of enraging their party leadership as Anderson or Nadine Dorries. Norman Tebbit was no mere deputy to the Conservative party chairmanship, and his rise to senior Cabinet membership did not blunt his rhetoric.

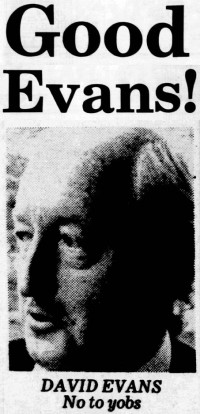

However, if there was a figure who liked to offend with a relish that might make Anderson or his GB News colleagues blush, and who also epitomised whatever is the British version of the American dream, it was David Evans, MP for Welwyn Hatfield in Hertfordshire from 1987 to 1997, who died exactly fifteen years ago. Born in Edmonton, north-east London – as his accent proudly attested – his careers as cricketer for Gloucestershire and Warwickshire and as footballer for Aston Villa were short-lived, but in his mid-twenties he founded a cleaning firm that made him a multi-millionaire.

By the time he became an MP, Evans was already a public figure as chairman of Luton Town FC, then in their previous spell as the poor relation of the English top division. After a notorious riot (even for the hooligan-heavy 1980s) at a home FA Cup tie against Millwall, Evans introduced two measures – banning away fans from Luton games and introducing ID cards for home supporters – that were anathema within football but welcomed by the government, who attempted to have the membership scheme made compulsory nationwide.

That might not have been a coincidence, according to Luton’s then manager David Pleat, who later told the Guardian: ‘We became pariahs. He was a naughty boy, David. He was Mrs Thatcher’s plaything. He wanted a safe Tory seat. I didn’t agree with it but there was no discussion, no debate.’

Either way, Evans was in position when a vacancy arose at Welwyn Hatfield, and while he was to rise no higher on the ministerial ladder than PPS at various departments, he achieved a prominence that was far from junior.

He of course leant into the issue that made him well known in the first place. Evans spoke in praise of his own football ID Cards scheme in his second Commons contribution on 4 November 1987. And then again on 16 November 1987. And on 20 January 1988. And 17 February 1988. And 16 June 1988. And 12 July 1988. And 10 February 1989. And so on.

In fact, it soon became government policy, meeting almost universal opposition within football (save for the Luton chairman himself). However, the scheme was eventually effectively ruled out by the Taylor Report, that followed the Hillsborough disaster, to the fury of Evans, who told Parliament that rather than all-seater stadia, football would be made much safer if ‘these hooligans were taken away and flogged’.

But Evans would hardly have gained public notoriety merely by limiting his pronouncements to soccer. ‘Giving twenty lashes per prisoner per year may be more appropriate [than prison itself],’ he advocated in one debate on crime, not forgetting to advocate the death penalty, corporal punishment in schools, National Service (‘One practice from the [European] Community that I would grasp with open arms’), and in case those rather liberal policies drifted into cliché: ‘The rapist should have his goolies removed.’

Tony Banks, an opposite in terms of ideology if not necessarily outspokenness, responded: ‘As I listened to the honourable gentleman I realised that he is one of those who makes Ayatollah Khomeini seem like one of the bleeding-heart liberals of whom the honourable gentleman accuses our country of having.’

Banks, of course, did manage to find some sort of conventional respectability in later years, first with his stint as Minister of Sport and then in his role overseeing the House of Commons art collection before elevation to the Lords. This transformation from cheeky chappie to at least slightly distinguished cheeky chappie never happened for Evans, but he did actually try.

Politically he was more naturally aligned to Margaret Thatcher than John Major, but it was under his fellow working-class football and cricket fan (though Evans was a committee member of Middlesex CCC rather than Major’s Surrey) that he at least got a step on the ministerial ladder, though very much the bottom rung as a PPS for the PM’s future nemesis John Redwood at various departments between 1990 and 1993.

Evans even did his best at acting the Major loyalist, asking in PMQs on 7 March 1991: ‘Does my right honourable friend agree that under his outstanding leadership we have become a united party determined to defeat inflation and the Labour party when the general election comes?’, continuing in the same vain until Speaker Bernard Weatherill, not for the only time when he was in the chair and Evans was on his feet, intervened: ‘I think that is enough.’

Evans’s trying-to-persuade-himself effusiveness was no more effective in making him a reliable loyalist than it was in assuaging Weatherill’s barely concealed impatience with such speeches. In the end Evans abandoned his role as Redwood’s bag-carrier and opted for election to the 1922 Committee executive. He did stand as a leadership loyalist to oust Maastricht rebel Sir George Gardiner, but was soon settling into a role as another of the bastards out there for Major.

Barely was Evans on the 1922 executive than he was fuming to the News of the World that minister Tim Yeo should step down for having an affair, saying: ‘If ministers cannot adhere to the moral standards they are preaching at us every day, they ought not to stay in office.’

Any hope he might be taken seriously was fading, though. A call just ahead of the 1994 local elections for six Cabinet sackings prompted fellow Tory MP Gyles Brandreth – a man in touch with received opinion within the parliamentary party – to reflect in his diaries: ‘We know Evans is a music-hall turn who likes to play the loutish Essex man for a laugh.’ Brandreth, lest anyone should think that from him ‘music-hall turn’ might be a compliment, added: ‘In my opinion, he’s a tosspot.’

By the following summer, Evans was even turning on his fellow 1922 executives for backing Major against Redwood in the leadership contest, declaring: ‘[Major] has even set his own office up, to canvass all the backbenchers, so I don’t feel loyalty as part of that executive any more … I’m quite prepared to say to you that I won’t be endorsing the Prime Minister’s candidacy myself.’

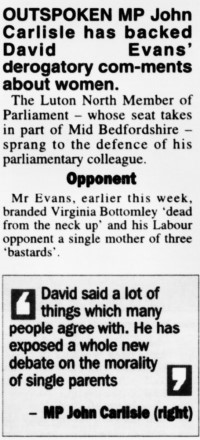

As the 1997 election approached, came an own goal by Evans worthy even of that of his former Luton striker Mick Harford. With voting less than two months away, and Welwyn and Hatfield vulnerable to the likely Labour swing, Evans set his stall out in an interview at Stanborough School in his constituency, which a pupil just happened to tape. He called for the castration of rapists (not hesitating to mention the race of a recent such offender), he questioned the innocence of the Birmingham Six, and he dismissed his Labour rival Melanie Johnson’s chances since she was ‘a single girl, lives with her boyfriend, three bastard children, lives in Cambridge’.

An equal opportunities offender, Evans also turned his fire on some Right Honourable friends, saying Secretary of State for National Heritage, Virginia Bottomley, was ‘dead from the neck upwards’ and Major himself ‘vindictive and unforgiving’.

Major, unforgivingly if not overly vindictively, agreed at a press conference the next morning that he ‘condemned unreservedly’ Evans’ remarks, and Chief Whip Alastair Goodlad was soon in touch. Evans issued apologies to Major and Bottomley (who called it ‘gallant’) and claimed his comments had been taken ‘out of context’.

Evans was not so sorry about his comments on Johnson, doubling down: ‘If you have three children out of wedlock, whether you like it or not they are bastards. It was a light-hearted interview.’

However Johnson, who Evans had claimed in the original interview did not ‘have a chance in hell’ of unseating him due to her moral depravity of living in sin/Cambridge, did in fact top the poll in Welwyn Hatfield, and went on to beat a certain Grant Shapps four years later before the tables were turned in 2005. In her maiden speech, she graciously said that ‘Mr. Evans could be personally very charming’, before a dig of a more subtle kind than her predecessor favoured: ‘I am a firm believer in diversity and my own style will be a little different from his. As a mother of three, I can assure the House that my children will help to keep my feet on the ground.’

The unwise remarks at Stanborough School probably did not in themselves lose Evans his seat, but they were to prove directly costly in another way. The Birmingham Six, who since their successful appeal against conviction for the pub bombings had won libel actions against the Sunday Telegraph and the Sun, successfully sued Evans, and the now former MP paid them undisclosed damages and apologised in the High Court.

Evans by then had returned to business, retiring in 2002, six years before his death. By then the Conservative Party was firmly back in the hands of public schoolboys with socially liberal leanings, and Shapps was an MP for Welwyn Hatfield slightly less likely, even in his most combative moods, to describe himself as ‘a very right-wing disciplinarian’.

Public schoolboys, and indeed Shapps himself, may remain at the Tory helm fifteen years on, but something of the Evans spirit has returned to their parliamentary parry, although mostly hailing from the north of England rather than just north of London. While Evans was not short of outlets to air his views, either deliberately in the Commons chamber or a to a tabloid hack, or inadvertently in a sixth-form general studies class, social media and a regular GB News gig might well have given him a national celebrity or at least notoriety beyond even that he achieved either as a football chairman or MP.

Evans, a man with an overlooked hinterland and success prior to politics, ended his decade in Parliament as rather a mocked figure, his party colleagues increasingly exasperated and opponents dismissive of his barbs, disappearing from view even as the likes of Gorman and Taylor remained in public consciousness (helped admittedly by having seats far safer than Evans could boast).

Was Evans an honest tribune, patronised and ignored in turn by a narrow effete political class inadvertently revealing their contempt for a class of people whose votes they seek, but opinions they disdain? Or is the easy fame gained by ignoring the conventions of public discourse a trap into which he (like a Lee Anderson) willingly stepped, whatever his previous motivation for entering politics?

A John Major or an Alan Johnson show that the route from working-class obscurity to the heights of government exists; without hiding their roots or even particularly modulating their accents, they made themselves serious figures. Then again both Major and Johnson generally steered clear of extremity of opinion; perhaps a more radical view is only truly taken seriously when put forward by a well-bred Tony Benn or a highly-educated Enoch Powell.

Which is not to say Evans was of that calibre or potential, but is a deviation from both received opinion and received pronunciation worthy of more than a comparison to a comic turn? Evans, however, who used his very last Parliamentary question to compare, in a tortured metaphor, the Labour party to monkeys, appears to have ultimately decided that was indeed why he was there.

Very good. Should be in a national publication.

LikeLike